***Official Houston Astros 2022-23 Offseason Thread***

1,107,692 Views |

12340 Replies |

Last: 1 yr ago by Beat40

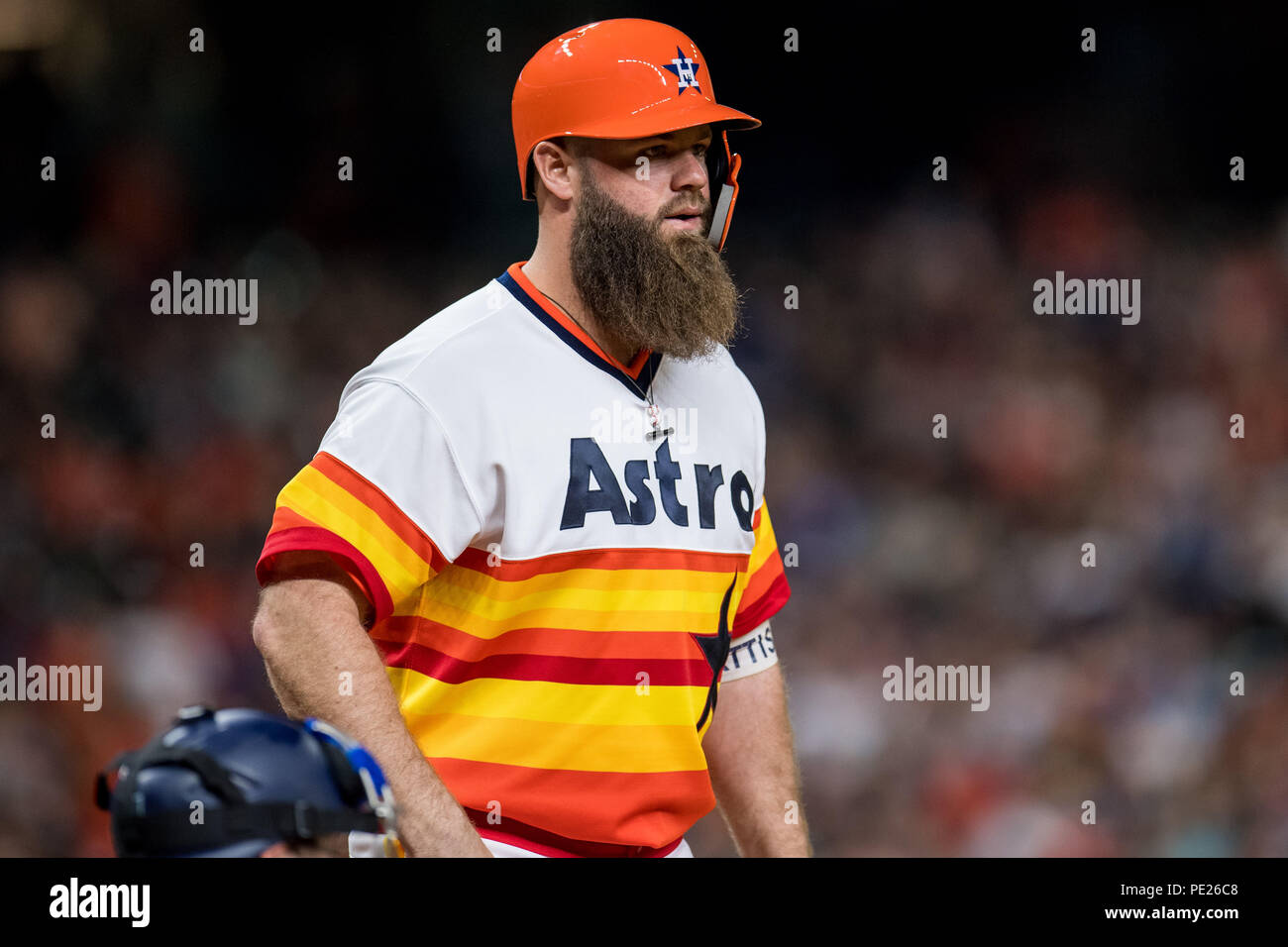

Bags need to stick to his current facial hair style and permanently drop the pube goatee

wangus12 said:

Don't care who she supports in football, but damn

https://instagr.am/p/CoD83bLI2g8

You have to delete the =

I believe she is from up there

very cool. I wish I had that kind of skill.bearkatag15 said:🤘🏽🤘🏽🤘🏽 https://t.co/56OefOVqqz pic.twitter.com/fmMmwS76lZ

— Ruben Valdez 🇲🇽🇺🇸 (@rubenvaldez_jr) January 30, 2023

This is pretty cool from the guy that did the photoshop for this

Also explains why both uniforms look so good… because they are the correct fit. When we wear the throwbacks in real life they are always two sizes too large and look like crap.

As opposed to what they were supposed to fit like

You just came up with a great off-season topic. Which Astro do you pick in a no-holds barred fight inside the octagon. Let's say for 3 rounds of 2 minutes per round.McInnis said:

Strange thing is that I couldn't stand those rainbow uniforms back when the Astros wore them all the time. They didn't look like real baseball uniforms to me. But over the years they've grown on me and I was kind of hoping they would break them out against Philly in game 6.

And +++ to all the comments on Joe Kelly. I might be embarrassed to admit how much I would pay to see him and CC get after it in a closed ring.

Only one choice.

I'm going to go with Cristen Javier. He has a good "dead eyes" look where you don't know when he's going to start swinging.

I knew Chris was a smart man.

Kyle Tucker +4000 on the Barstool Sportsbook to win AL MVP. Great batted ball data, no shift to worry about and a lineup full of guys who can protect him. Still only 26.

— Chris Castellani (@Castellani2014) January 31, 2023

The Porkchop Express said:You just came up with a great off-season topic. Which Astro do you pick in a no-holds barred fight inside the octagon. Let's say for 3 rounds of 2 minutes per round.McInnis said:

Strange thing is that I couldn't stand those rainbow uniforms back when the Astros wore them all the time. They didn't look like real baseball uniforms to me. But over the years they've grown on me and I was kind of hoping they would break them out against Philly in game 6.

And +++ to all the comments on Joe Kelly. I might be embarrassed to admit how much I would pay to see him and CC get after it in a closed ring.

Only one choice.

I'm going to go with Cristen Javier. He has a good "dead eyes" look where you don't know when he's going to start swinging.

My money is on Chas. Grew up with a twin in Philly. You know that kid has hands.

I'm taking the 6'1 225 lb Dominican.

That's one bad mofo

That's one bad mofo

Ag_07 said:

I'm taking the 6'1 225 lb Dominican.

That's one bad mofo

I agree. Abreu is scary and threw pure filth in the postseason.

Per TMZ, Actress Margot Robbie is reportedly dating World Series Champion Martin Maldonado 😳 pic.twitter.com/CSTvaD8bh8

— Space Lawyer (@rrossjd) January 30, 2023

Maybe she needed a slumpbuster

Jannelise would put a 6" shiv in Magot's eye if she got within 10 feet of Machete.

By the way, researching her picture led me to this solid gold Yuli Gurriel photo.

By the way, researching her picture led me to this solid gold Yuli Gurriel photo.

Harry Dunne said:Per TMZ, Actress Margot Robbie is reportedly dating World Series Champion Martin Maldonado 😳 pic.twitter.com/CSTvaD8bh8

— Space Lawyer (@rrossjd) January 30, 2023

Maybe she needed a slumpbuster

He can play as long as he wants

for anyone not yet in on the joke

https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2023/01/29/sports-world-margot-robbie-twitter-viral-meme

https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2023/01/29/sports-world-margot-robbie-twitter-viral-meme

https://ts.la/eric59704

I knew this was a running joke but wasn't sure where it came from...but does this also mean she doesn't believe tucker is a stud?07ag said:

for anyone not yet in on the joke

https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2023/01/29/sports-world-margot-robbie-twitter-viral-meme

I am mesmerized by this gif.BadAggie said:

The Tucker one is 100% true. All the others are fake.Lonestar_Ag09 said:I knew this was a running joke but wasn't sure where it came from...but does this also mean she doesn't believe tucker is a stud?07ag said:

for anyone not yet in on the joke

https://www.si.com/extra-mustard/2023/01/29/sports-world-margot-robbie-twitter-viral-meme

Pure conjecture, but the guys that are HOF cocksmen tend to not stick around one franchise like the marry early types. Jeter is the one exception I can think of.

Tucker marrying his very normal looking GF is a good omen.

Tucker marrying his very normal looking GF is a good omen.

The Astros have one game on Peacock this season: an Aug. 20 game against the Mariners at Minute Maid Park. 12:05 p.m. first pitch.

— Chandler Rome (@Chandler_Rome) January 31, 2023

I live the continued lack of logic by MLB on broadcasting. Whoever finally figured it out will be my least hated commissioner.

Any word on the apple tv games?

I think the networks have them by the balls for some reason. I'm speculating, but I don't really know why else they'd keep the blackout situation.

It's a deal with the regional networks. As I understand it, MLB doesn't control the overall product. The teams have individual deals with regional sports networks to carry X number of games per season. That usually leaves some for the MLB to cherry-pick for national broadcasts.Coby said:

I think the networks have them by the balls for some reason. I'm speculating, but I don't really know why else they'd keep the blackout situation.

https://instagr.am/p/CoFs0anpibj

The new crew

The new crew

Bulldog73 said:

I live the continued lack of logic by MLB on broadcasting. Whoever finally figured it out will be my least hated commissioner.

Teams make a boatload from the local TV deals. MLB makes a boatload from these major networks and streams for a few games. Having a 1 stop shop streaming service devalues those deals. We're stuck playing musical chairs trying to watch.

Yeah but not every boat is the same size. YES =/= ATT Sports SW. Thats the Titanic versus the S.S Minnow. And MLB owners do not want to play nice with each other and share. Its every man for himself.Farmer1906 said:Bulldog73 said:

I live the continued lack of logic by MLB on broadcasting. Whoever finally figured it out will be my least hated commissioner.

Teams make a boatload from the local TV deals. MLB makes a boatload from these major networks and streams for a few games. Having a 1 stop shop streaming service devalues those deals. We're stuck playing musical chairs trying to watch.

Mathguy64 said:Yeah but not every boat is the same size. YES =/= ATT Sports SW. Thats the Titanic versus the S.S Minnow. And MLB owners do not want to play nice with each other and share. Its every man for himself.Farmer1906 said:Bulldog73 said:

I live the continued lack of logic by MLB on broadcasting. Whoever finally figured it out will be my least hated commissioner.

Teams make a boatload from the local TV deals. MLB makes a boatload from these major networks and streams for a few games. Having a 1 stop shop streaming service devalues those deals. We're stuck playing musical chairs trying to watch.

True. Teams make different ticket, concession, & merch too. There will always be haves and have nots.

Brad Peacock needs an endorsement deal with Peacock

Still can't believe Siri never got a deal with Apple

Still can't believe Siri never got a deal with Apple

Athletic Offseason Grade:

Quote:

Houston Astros

Grade: B+

Nailing down the GM spot was huge for the organization, and Dana Brown is a well-regarded executive with a great background in scouting for a few successful organizations. The Astros also got better at first base by signing Jos Abreu to a three-year deal, but will his worst slugging against fastballs (by 100 points) in 2022 be more of a sign of age than the org thought? Also letting Justin Verlander go means not only losing some star power at the top of the rotation, but making Hunter Brown the one-man stop-gap if the team needs pitching depth. Last year's best starting rotation can probably handle it, though, so a good offseason writ large. Eno Sarris

If anyone is curious here is the article on the reporting of the sign stealing. No Astro fan should pay them a dime.

The following is an excerpt from "Winning Fixes Everything: How Baseball's Brightest Minds Created Sports' Biggest Mess," by Evan Drellich. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers LLC, 2023 Evan Drellich.

On Nov. 12, 2019, The Athletic broke the story of the Astros' illegal sign-stealing in a report by Drellich and Ken Rosenthal. For the first time, details of their reporting process are explained.

There was probably a better use of my time than trudging up and down the long stairs of the converted schoolhouse I lived in for yet another cigarette in the Boston cold, but I needed to escape somewhere. It was February 2019, and I had just been fired. My reporting future was uncertain, my bank account was dwindling, and I was gaining weight rapidly. Every day, I was left to wonder whether I'd passed on the biggest story of my life.

A few months earlier, in October 2018, I was a Red Sox beat writer. In the penultimate round of the Major League Baseball postseason, the Sox were coincidentally playing the Houston Astros, a team I had once covered. The Astros at this point were the defending World Series champions, after winning the first title in franchise history in 2017.

There was one massive problem, I learned during that 2018 postseason. Sitting in a hotel room within walking distance of the Astros' stadium, I spoke with people who had firsthand knowledge of how the Astros had cheated in that championship season. These were not sources on the outside pointing fingers, but people who knewwho had lived it.

I learned how the Astros used a camera in center field to zoom in on the signs the catcher flashed the pitcher before the pitch. How the Astros had set up a television monitor near their dugout, where the players sit during games, to be able to see that video feed, and how they brazenly banged on a garbage can with a baseball bat and other devices to communicate what they gleaned from that screen. It was an advantage, many players felt, to know what was coming, be it a straight fastball or a bending curveball. And to use technology to gain that knowledge was beyond the pale.

This wasn't just one player breaking the rules, either. This was a World Serieswinning team that had collectively cheated, and the public didn't know it.

I was floored. It was a massive story, the kind, frankly, many reporters dream of, and some might even dread. I was confident in everything I had at the outsetindeed, it all proved to be true. But to get a story done, I would need further corroboration.

One Astros source warned of the context of cheating in the sport, an encouragement that in hindsight could have both been earnest, but also self-serving, meant to deflect attention away from what the Astros had done. Nonetheless, I wanted to learn for myself and include it in my reportingin what environment did this behavior arise?

During batting practice before one of the Red SoxAstros playoff games at Houston's Minute Maid Park in 2018, Houston's general manager, Jeff Luhnow, stood near the top step of the Astros dugout. He was the architect of the team, and I tried to get his attention as he was walking away from me. "You won't find anything," he said defensively, making clear he wouldn't talk to me.

Luhnow quickly disappeared down the dugout steps into the tunnel, walking, ironically, right into the area where I had just learned the team had conducted its cheating.

On the night the Red Sox won that series in Houston, eliminating the Astros, I shot my television spots on the dimly lit, empty field. The Astros' dugout, on the first-base side, was a short distance away. Down a few steps to the tunnel I went, to a short but wide corridor that leads to the locker room. I wanted to check out the scene of the prior year's crime for myself.

There was the garbage can, near to the wall on my right, and an empty space with wires hanging nearby indicated where a TV had once beenexactly as the setup had been described to me. I took a few photos, hoping someday one would accompany a story.

The Red Sox had moved on to the World Series, where they faced the Los Angeles Dodgers. I met with a pair of MLB officials at Dodger Stadium, trying to understand what MLB was undertaking to combat electronic sign-stealing. I told them I had multiple accounts of the Astros stealing signs via electronic means in the prior year.

"I think that every club is always suspicious, but again" one official said.

I cut the official off: "This is from within the Astros."

"Within the Astros, they're acknowledging that they've done this?" one shot back, surprised.

Yes.

"They have acknowledged that?" one said. "I mean, I can't speak to that. I mean, to our knowledgeyou have your information, and we have ours, and that's all we can go off. As to whether that has occurred, to our knowledge we are completely unaware. I am confident in the measures that we've taken."

I was curious how seriously the league would treat the matter and was told it would ultimately be up to Commissioner Rob Manfred. I wasn't contacting the league attempting to steer its own investigative work, to be a friendly tipster. Rather, were MLB looking deeper into the Astros' cheating, and I could ascertain as much, then I might have an entre to a story sooner rather than later.

It was one of a handful of brief communications I had in 2018 with baseball's central office over what I understood had happened.

"If you can tell your sources that they shouldif they want to speak to the commissioner's office, we're all ears," a different official told me once the World Series ended. "The problem is, nobody talks to us."

Of course, no such redirection would take place. It's not a reporter's job to steer sources to the league. But it was clear to me the league was not of a mind to act.

As the offseason began, I was leery of publishing what I had learned about the Astros to that point. For one, none of my sources were on the record, and if the story was going to be based solely on unnamed sources, I wanted more than I had at the time. I also knew that finding someone to go on the record about cheating might be impossible, but I still wanted to see if that person was out there.

I also considered how the story would be received, and, frankly, whether it would be believed. I was no longer in Houston, but covering a rival team in Boston. The Astros, I knew well, were aggressive with the media, and I suspected they would do everything in their power to attack me and my reporting.

During my time covering the Astros, from late 2013 into 2016, they were a controversial franchise. I reported on questions about their management culture and decision-making with the support of my newspaper, the Houston Chronicle, which was the only outlet in the city that covered the team on the road and was not also owned by the team.

The Astros had tried to bully me into submission. In 2015, the owner of the team and the head spokesperson attempted to remove me from the beat in a meeting with a pair of Chronicle editors simply because they didn't like my coverage. Thankfully, my editors stood by me.

Now, the truth is the truth, and years later, I wasn't going to back away from reporting on the Astros' cheating for fear of receptionnot alone. But there was one other major wrinkle. I didn't think the outlet I was working for at the time was equipped to support this reporting.

This was not a major newspaper with the backbone and support staff for a major investigation. I was working for a TV station whose primary reason for existence was televising Boston Celtics basketball games and reacting to sports-talk radio.

I took the conservative route, and really, the only route I could; to keep reporting. I wrote a general piece on electronic sign-stealing in November 2018.

Very quickly, my doubts about the support I had at NBC Sports Boston proved correct. When they fired me in February 2019, I was blindsided, but perhaps I shouldn't have been.

Days passed slowly with some part-time work on the radio in Boston, talking to fans after games: "Six-one-seven, seven-seven-nine, seven-ninety-three-seven, taking your calls up until midnight on your home for Red Sox baseball. Chris in Natick, what's up, Chris?"

Eventually, The Athletic, now owned by the New York Times, brought me on. In my new role, I would be working closely with the best baseball writer in the world, Ken Rosenthal. He's recognizable by the bow ties he wears for charity during Fox national telecasts, including the World Series.

Together, we would pick up my reporting on the Astros.

Once Ken and I paired up, there was an obvious choice to make. In instances where we thought we might have only one chance to get someone to pick up the phone, I wanted Ken to be the one to make that call. His cachet in the industry is unmatched.

Thirteen months after I had started to investigate the Astros' cheating, the endgame of our reporting was intense. Ken spoke to Danny Farquhar, the pitcher who had heard the banging while on the mound in September 2017, and Farquhar went on the record. The chances of finding someone who had been on the Astros who would also go on the record were slim, and we knew that the whole time. But we were going to keep trying.

Mike Fiers's name had come up in 2018 and did so again in 2019. Just three days before we wound up publishingand within just a few hours of his conversation with FarquharKen got Fiers on the phone.

"We are writing about sign-stealing in 2017," Ken told Fiers, then started to explain.

"I don't even know where to start. I don't understand," Fiers said. "What are you guys doing?"

Ken read him part of an early version of the story, with the details of the scheme.

"That's pretty much what I know," Fiers said. "I never read the rulebook fully. I don't know if that was in there or what the rule actually was. But they were advanced and willing to go above and beyond to win. As a pitcher, you have no say in it. It's not helping you at all. The pitching staff isn't using that to help them. And it's tough. Also, there were guys who didn't like it. There are guys who don't like to know and guys who do."

Ken asked Fiers if he was comfortable being quoted.

"Well, that's the whole thing about this. I don't want to be put out there like that. But they already know, so honestly, I don't really care anymore," Fiers said, referring to the fact the Astros already knew he had spoken up to the A's and Tigers. "I just want the game to be cleaned up a little bit because there are guys who are losing their jobs because they're going in, they're not knowing. Young guys getting hit around in the first couple of innings starting a game, and then they get sent down. It's bulls on that end. It's ruining jobs for younger guys. The guys who know are more prepared. But most of the people don't. That's why I told my team. We had a lot of young guys with Detroit trying to make a name and establish themselves. I wanted to help them out and say, 'Hey, this stuff really does go on. Just be prepared.'"

Fiers, to his immense credit, stood by his words and never tried to back out before the investigation ran. He helped change the sport, and the toll ostensibly has been heavy for him.

At the time Ken spoke to Fiers, we were preparing to publish our findings without his account. It's impossible to say exactly how the world would have reacted to the story had Ken not spoken to himif all the sources had been unnamed. But the facts of the story had already been ascertained, and we had Farquhar's account.

Within hours of the story being published on November 12, the internet was brimming with not only our explanation of how the 2017 Astros had broken the rules but also footage compiled by Jomboy, a Yankees fan named Jimmy O'Brien who was already known in baseball circles for his savvy in reviewing video and sound from games. Jomboy put together a clip where the bangs on the trash can could be heard.

Whether Fiers was quoted or not, it seems unlikely to me that MLB would have been able to ignore the general outcry. But our investigation was still in a much better position with Fiers on the record. His name helped validate everything instantly, making it harder for anyone to try to shove the story aside.

Ultimately, Ken and I were conservative in what we published on November 12. For example: Although we had been given an account of the Astros' road sign-stealing system, the baserunner system, we didn't have the same level of confirmation of that as we did for the home system and so figured it was safer to wait. We simply noted, "The Astros did not use the same system in away games."

Ken and I felt strongly that it was important to try to address the context, the sense in Houston and elsewhere that the Astros had not been the only ones to engage in at least some form of wrongdoing. We went down that road in the top portion of the story, and in the headline: "The Astros Stole Signs Electronically in 2017Part of a Much Broader Issue for Major League Baseball."

We also knew that we had more reporting to do. We didn't yet have firsthand accounts of any other team behaving improperly, but we were going to continue to look. In January 2020, we published an investigation into the Red Sox' improper use of their video room in 2018, the year they won the World Series. But it remains the case that no team has been shown, through firm reporting or accounts, to have done something as blatant as Houston. (Ultimately, whether severity matters in cheating, I believe, is up to the reader. Is a little cheating better than a lot of cheating?)

During our investigations, not everyone answered their phone eagerly. "I'll go till the end to crush you people," one person told us. "Trust me."

The following is an excerpt from "Winning Fixes Everything: How Baseball's Brightest Minds Created Sports' Biggest Mess," by Evan Drellich. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers LLC, 2023 Evan Drellich.

On Nov. 12, 2019, The Athletic broke the story of the Astros' illegal sign-stealing in a report by Drellich and Ken Rosenthal. For the first time, details of their reporting process are explained.

There was probably a better use of my time than trudging up and down the long stairs of the converted schoolhouse I lived in for yet another cigarette in the Boston cold, but I needed to escape somewhere. It was February 2019, and I had just been fired. My reporting future was uncertain, my bank account was dwindling, and I was gaining weight rapidly. Every day, I was left to wonder whether I'd passed on the biggest story of my life.

A few months earlier, in October 2018, I was a Red Sox beat writer. In the penultimate round of the Major League Baseball postseason, the Sox were coincidentally playing the Houston Astros, a team I had once covered. The Astros at this point were the defending World Series champions, after winning the first title in franchise history in 2017.

There was one massive problem, I learned during that 2018 postseason. Sitting in a hotel room within walking distance of the Astros' stadium, I spoke with people who had firsthand knowledge of how the Astros had cheated in that championship season. These were not sources on the outside pointing fingers, but people who knewwho had lived it.

I learned how the Astros used a camera in center field to zoom in on the signs the catcher flashed the pitcher before the pitch. How the Astros had set up a television monitor near their dugout, where the players sit during games, to be able to see that video feed, and how they brazenly banged on a garbage can with a baseball bat and other devices to communicate what they gleaned from that screen. It was an advantage, many players felt, to know what was coming, be it a straight fastball or a bending curveball. And to use technology to gain that knowledge was beyond the pale.

This wasn't just one player breaking the rules, either. This was a World Serieswinning team that had collectively cheated, and the public didn't know it.

I was floored. It was a massive story, the kind, frankly, many reporters dream of, and some might even dread. I was confident in everything I had at the outsetindeed, it all proved to be true. But to get a story done, I would need further corroboration.

One Astros source warned of the context of cheating in the sport, an encouragement that in hindsight could have both been earnest, but also self-serving, meant to deflect attention away from what the Astros had done. Nonetheless, I wanted to learn for myself and include it in my reportingin what environment did this behavior arise?

During batting practice before one of the Red SoxAstros playoff games at Houston's Minute Maid Park in 2018, Houston's general manager, Jeff Luhnow, stood near the top step of the Astros dugout. He was the architect of the team, and I tried to get his attention as he was walking away from me. "You won't find anything," he said defensively, making clear he wouldn't talk to me.

Luhnow quickly disappeared down the dugout steps into the tunnel, walking, ironically, right into the area where I had just learned the team had conducted its cheating.

On the night the Red Sox won that series in Houston, eliminating the Astros, I shot my television spots on the dimly lit, empty field. The Astros' dugout, on the first-base side, was a short distance away. Down a few steps to the tunnel I went, to a short but wide corridor that leads to the locker room. I wanted to check out the scene of the prior year's crime for myself.

There was the garbage can, near to the wall on my right, and an empty space with wires hanging nearby indicated where a TV had once beenexactly as the setup had been described to me. I took a few photos, hoping someday one would accompany a story.

The Red Sox had moved on to the World Series, where they faced the Los Angeles Dodgers. I met with a pair of MLB officials at Dodger Stadium, trying to understand what MLB was undertaking to combat electronic sign-stealing. I told them I had multiple accounts of the Astros stealing signs via electronic means in the prior year.

"I think that every club is always suspicious, but again" one official said.

I cut the official off: "This is from within the Astros."

"Within the Astros, they're acknowledging that they've done this?" one shot back, surprised.

Yes.

"They have acknowledged that?" one said. "I mean, I can't speak to that. I mean, to our knowledgeyou have your information, and we have ours, and that's all we can go off. As to whether that has occurred, to our knowledge we are completely unaware. I am confident in the measures that we've taken."

I was curious how seriously the league would treat the matter and was told it would ultimately be up to Commissioner Rob Manfred. I wasn't contacting the league attempting to steer its own investigative work, to be a friendly tipster. Rather, were MLB looking deeper into the Astros' cheating, and I could ascertain as much, then I might have an entre to a story sooner rather than later.

It was one of a handful of brief communications I had in 2018 with baseball's central office over what I understood had happened.

"If you can tell your sources that they shouldif they want to speak to the commissioner's office, we're all ears," a different official told me once the World Series ended. "The problem is, nobody talks to us."

Of course, no such redirection would take place. It's not a reporter's job to steer sources to the league. But it was clear to me the league was not of a mind to act.

As the offseason began, I was leery of publishing what I had learned about the Astros to that point. For one, none of my sources were on the record, and if the story was going to be based solely on unnamed sources, I wanted more than I had at the time. I also knew that finding someone to go on the record about cheating might be impossible, but I still wanted to see if that person was out there.

I also considered how the story would be received, and, frankly, whether it would be believed. I was no longer in Houston, but covering a rival team in Boston. The Astros, I knew well, were aggressive with the media, and I suspected they would do everything in their power to attack me and my reporting.

During my time covering the Astros, from late 2013 into 2016, they were a controversial franchise. I reported on questions about their management culture and decision-making with the support of my newspaper, the Houston Chronicle, which was the only outlet in the city that covered the team on the road and was not also owned by the team.

The Astros had tried to bully me into submission. In 2015, the owner of the team and the head spokesperson attempted to remove me from the beat in a meeting with a pair of Chronicle editors simply because they didn't like my coverage. Thankfully, my editors stood by me.

Now, the truth is the truth, and years later, I wasn't going to back away from reporting on the Astros' cheating for fear of receptionnot alone. But there was one other major wrinkle. I didn't think the outlet I was working for at the time was equipped to support this reporting.

This was not a major newspaper with the backbone and support staff for a major investigation. I was working for a TV station whose primary reason for existence was televising Boston Celtics basketball games and reacting to sports-talk radio.

I took the conservative route, and really, the only route I could; to keep reporting. I wrote a general piece on electronic sign-stealing in November 2018.

Very quickly, my doubts about the support I had at NBC Sports Boston proved correct. When they fired me in February 2019, I was blindsided, but perhaps I shouldn't have been.

Days passed slowly with some part-time work on the radio in Boston, talking to fans after games: "Six-one-seven, seven-seven-nine, seven-ninety-three-seven, taking your calls up until midnight on your home for Red Sox baseball. Chris in Natick, what's up, Chris?"

Eventually, The Athletic, now owned by the New York Times, brought me on. In my new role, I would be working closely with the best baseball writer in the world, Ken Rosenthal. He's recognizable by the bow ties he wears for charity during Fox national telecasts, including the World Series.

Together, we would pick up my reporting on the Astros.

Once Ken and I paired up, there was an obvious choice to make. In instances where we thought we might have only one chance to get someone to pick up the phone, I wanted Ken to be the one to make that call. His cachet in the industry is unmatched.

Thirteen months after I had started to investigate the Astros' cheating, the endgame of our reporting was intense. Ken spoke to Danny Farquhar, the pitcher who had heard the banging while on the mound in September 2017, and Farquhar went on the record. The chances of finding someone who had been on the Astros who would also go on the record were slim, and we knew that the whole time. But we were going to keep trying.

Mike Fiers's name had come up in 2018 and did so again in 2019. Just three days before we wound up publishingand within just a few hours of his conversation with FarquharKen got Fiers on the phone.

"We are writing about sign-stealing in 2017," Ken told Fiers, then started to explain.

"I don't even know where to start. I don't understand," Fiers said. "What are you guys doing?"

Ken read him part of an early version of the story, with the details of the scheme.

"That's pretty much what I know," Fiers said. "I never read the rulebook fully. I don't know if that was in there or what the rule actually was. But they were advanced and willing to go above and beyond to win. As a pitcher, you have no say in it. It's not helping you at all. The pitching staff isn't using that to help them. And it's tough. Also, there were guys who didn't like it. There are guys who don't like to know and guys who do."

Ken asked Fiers if he was comfortable being quoted.

"Well, that's the whole thing about this. I don't want to be put out there like that. But they already know, so honestly, I don't really care anymore," Fiers said, referring to the fact the Astros already knew he had spoken up to the A's and Tigers. "I just want the game to be cleaned up a little bit because there are guys who are losing their jobs because they're going in, they're not knowing. Young guys getting hit around in the first couple of innings starting a game, and then they get sent down. It's bulls on that end. It's ruining jobs for younger guys. The guys who know are more prepared. But most of the people don't. That's why I told my team. We had a lot of young guys with Detroit trying to make a name and establish themselves. I wanted to help them out and say, 'Hey, this stuff really does go on. Just be prepared.'"

Fiers, to his immense credit, stood by his words and never tried to back out before the investigation ran. He helped change the sport, and the toll ostensibly has been heavy for him.

At the time Ken spoke to Fiers, we were preparing to publish our findings without his account. It's impossible to say exactly how the world would have reacted to the story had Ken not spoken to himif all the sources had been unnamed. But the facts of the story had already been ascertained, and we had Farquhar's account.

Within hours of the story being published on November 12, the internet was brimming with not only our explanation of how the 2017 Astros had broken the rules but also footage compiled by Jomboy, a Yankees fan named Jimmy O'Brien who was already known in baseball circles for his savvy in reviewing video and sound from games. Jomboy put together a clip where the bangs on the trash can could be heard.

Whether Fiers was quoted or not, it seems unlikely to me that MLB would have been able to ignore the general outcry. But our investigation was still in a much better position with Fiers on the record. His name helped validate everything instantly, making it harder for anyone to try to shove the story aside.

Ultimately, Ken and I were conservative in what we published on November 12. For example: Although we had been given an account of the Astros' road sign-stealing system, the baserunner system, we didn't have the same level of confirmation of that as we did for the home system and so figured it was safer to wait. We simply noted, "The Astros did not use the same system in away games."

Ken and I felt strongly that it was important to try to address the context, the sense in Houston and elsewhere that the Astros had not been the only ones to engage in at least some form of wrongdoing. We went down that road in the top portion of the story, and in the headline: "The Astros Stole Signs Electronically in 2017Part of a Much Broader Issue for Major League Baseball."

We also knew that we had more reporting to do. We didn't yet have firsthand accounts of any other team behaving improperly, but we were going to continue to look. In January 2020, we published an investigation into the Red Sox' improper use of their video room in 2018, the year they won the World Series. But it remains the case that no team has been shown, through firm reporting or accounts, to have done something as blatant as Houston. (Ultimately, whether severity matters in cheating, I believe, is up to the reader. Is a little cheating better than a lot of cheating?)

During our investigations, not everyone answered their phone eagerly. "I'll go till the end to crush you people," one person told us. "Trust me."

Was excited to see Astros trending - did we get a catcher? Sign some prospects? Picked to win the whole thing again? Nope - just Ken Rosenthal, Evan Derelict, and The Athletic touting a new book about - gasp - the 2017 Astros (and to a much much lesser extent other teams). Clowns looking for clicks.

Just an FYI if anyone wants to read an athletic story. Click a link to the story, and immediately click Ctrl+A then Ctrl+C. From there paste into Word or somewhere to read it. It just has to be quick enough to register before the paid log in pops up.

Eh, pretty much what we already know - they didn't really care to see if any other clubs were doing something similar. By the time they did, everything was so public with punishments and whatnot being known that no other team was ever going to talk.

Also, it's one writer who had an axe to grind against management that broke it. That part also reveals why he wasn't keen on trying to see if it was a much larger league wide problem.

I'm sure Evan felt pretty good for being able to take Lunhow down.

He and Ken could have addressed the context of the sign stealing at the start of their article, but if I recall correctly, it was thrown in as a one liner or a small single paragraph at the end of the article. All intent to pin it on the organization that he had previously written about with character issues from his assessment and the organization that tried to get him fired. He can say what he wants, he didn't really care about the league as a whole. He saw an opportunity to strike back and he did.

Also, it's one writer who had an axe to grind against management that broke it. That part also reveals why he wasn't keen on trying to see if it was a much larger league wide problem.

I'm sure Evan felt pretty good for being able to take Lunhow down.

He and Ken could have addressed the context of the sign stealing at the start of their article, but if I recall correctly, it was thrown in as a one liner or a small single paragraph at the end of the article. All intent to pin it on the organization that he had previously written about with character issues from his assessment and the organization that tried to get him fired. He can say what he wants, he didn't really care about the league as a whole. He saw an opportunity to strike back and he did.