143 Years ago today 40 Irish-immigrant artillerists spared the State of Texas from an invasion by Union forces in what Confederate President Jefferson Davis termed the “Thermopylae of the Confederacy.” Lt. Richard “Dick” Dowling and the Davis Guards defeated an advanced Union invasion force of 20 vessels and 5,000 men. But unlike the Greeks at Thermopylae, who were all slaughtered, not a man was lost by the Confederate forces. They incapacitated and captured two Union gunboats, three hundred and fifty prisoners and sent the rest of the invasion force scurrying back to New Orleans with their tails between their legs. The expert marksmanship of these Texas artillerists would create yet another Texas legend in a lopsided battle that went the other way, invalidating Voltaire’s famous maxim of "God is always on the side of the heaviest battalions."

Battle of Sabine Pass as portrayed in Harper’s Weekly:

In the spring of 1863, the Confederate chief engineer for East Texas, Major Julius Kellersberg, arrived at Sabine City with orders to construct Fort Griffin to guard Sabine Pass from a potential Yankee invasion. Upon arrival, he found the village largely deserted. Its two sawmills, railway station, roundhouse, many residences and supply of sawed lumber had been burned the previous October by Federal naval forces who had briefly occupied the town, until malaria drove them away.

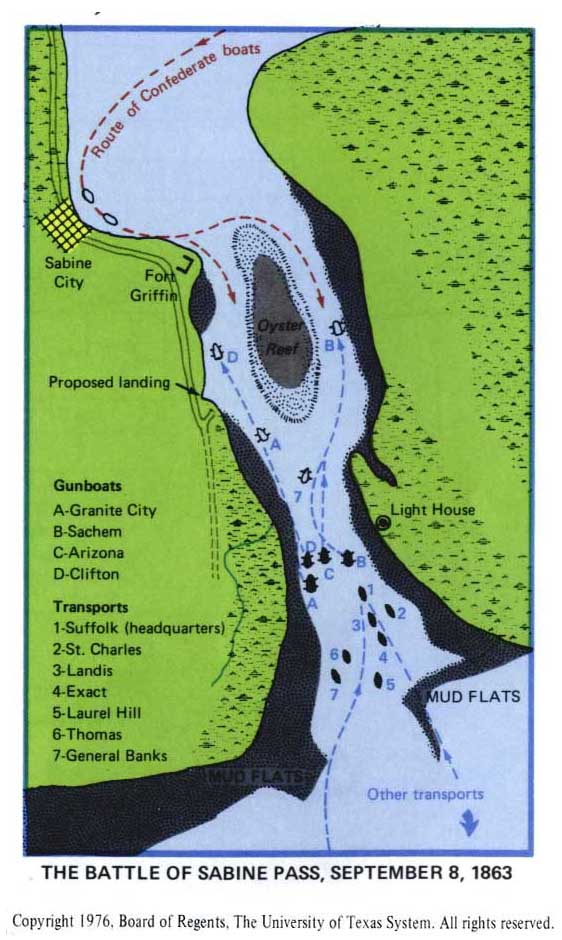

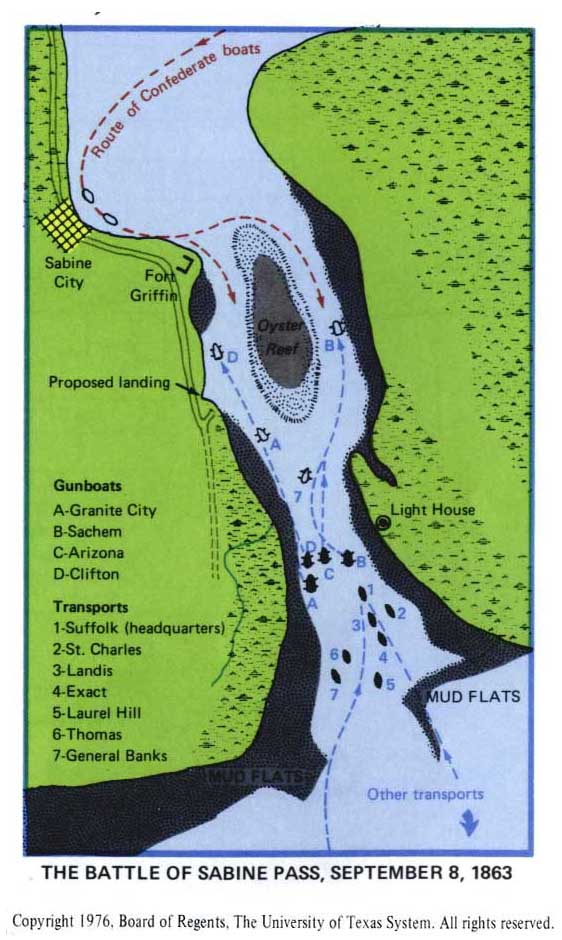

Civil War Map of Sabine Pass:

Kellersberg looked at a previous fort built in the pass, Ft. Sabine and dismissed its location and construction immediately (it had also been dismantled by the U.S. Navy to a certain extent). For a new redoubt site, Kellersberg chose a point where the ship channel made a sharp right turn. This location would permit the new mud fort's guns to traverse across a broader arc of about 270 degrees. He brought with him from Houston a work force of about 500 conscripted slaves and a staff of Confederate engineers. For construction material, there was a supply of saw logs, crossties, railroad iron, and oyster shell, but no armament or munitions. Fort Sabine had been at the point where the Sabine channel split into the Texas and Louisiana channels, divided as it was by a shallow oyster shell reef that obstructed the middle passage. The new fort would be constructed where the channels exited a mile farther north.

The only artillery available were two old field guns, of 6-pound and 12-pound size, left over from the Mexican War and much too small for coastal defense against invading Union warships. Kellersberg directed that two 24-pound long iron guns mounted at Fort Grigsby near Port Neches, Tx. and another pair of 32-pound brass howitzers at a fort on the Sabine River, 12 miles south of Orange be transferred to Sabine Pass.

One day during the construction, an old fisherman told Kellersberg about two 32-pound iron guns that had been buried a year earlier when Fort Sabine had been abandoned. The engineer had seen these cannons during an inspection the previous year but knew as well that they had been spiked before the fort was abandoned. He feared that they had been damaged beyond repair, and was also aware that if his new installation were to be defended properly, he must acquire larger weapons, although he knew that none were available at that moment.

Together the fisherman and Kellersberg went to the site of the old fort and the fisherman showed the engineer the place where the guns were buried. After some probing, they located the buried weapons as well as a large supply of 32-pound solid shot cannon balls. As he had feared, the damage to the guns was considerable. Each had been spiked with round files; the trunnions (swivels) had been cut away and one barrel had been wedged with a cannon ball. Since Kellersberg had previously interspersed wooden dummies ('quakers') with real artillery among Galveston's beach defenses, Kellersberg was reluctant to throw these damaged pieces away. At the first opportunity, he took them to the Confederate foundry in Galveston.

At home in Galveston, his chief, Col. Valery Sulakowski, a veteran of the Austrian Army and the organizer of the 1st Texas Rocket Battery (that’s a story for another day) advised strongly against trying to repair the rusted weapons. Still reluctant to dispose of them, Kellersberg consulted the local foundry's chief machinist. The foundryman attacked the problem with tremendous vigor. Day and night, he and Kellersberg hurried to complete the repairs, becasue already reports had reached Gen. John Bankhead “Prince John” Magruder's headquarters in Houston that the Federals were expected to turn their attention to the Texas coast.

“Prince John” Magruder, Confederate Commander of the Department of East Texas:

Repairs to the big guns required molding special 16-inch iron rings and stretching them over the barrels while they were heated and still glowing red. Then a groove one-half inch deep and one and one-half inches wide was twisted into each barrel over which each of the threaded wrought iron rings was stretched. The greatest hazard lay in boring the grooves too deep, which might weaken the barrels' ability to withstand the concussion, causing them to explode when fired.

Shortly afterward, Major Kellersberg loaded the repaired cannons along with a supply of shells and solid shot on the train bound for Beaumont. While en route to Sabine City, he gave each gun two coats of paint in order to save time. Two days later, the smoothbore weapons were mounted on gun carriages in Fort Griffin and placed in firing position on the fort's parapets along its sawtooth front. The cannons survived test firings and Kellersberg drove white markers near the end of the Texas and Louisiana channels on each side of the oyster reef to indicate the guns' maximum range.

When the engineer returned to Galveston, his fears were not dimmed completely and he recorded in his German-language memoirs that he spent many sleepless nights afterward worried about how these guns might perform.

At the same time Kellersberg was building Fort Griffin in Sabine Pass in May, 1863, Magruder began a systematic reduction of Confederate forces at Sabine Pass even though he felt an attack was imminent. Several companies of Spaight's Battalion were transferred to Opelousas, La., where General William B. Franklin was leading a Union invasion up the Bayou Teche. Initially Magruder sent Col. William F. Griffin (for whom the fort was named) and his battalion from Galveston to Sabine Pass. But when Comanche Indians began attacking the homes of Griffin's soldiers, west of Fort Worth during the early summer, the battalion threatened to desert or mutiny unless they were sent back to Tarrant County to subdue the Indians. Magruder reluctantly (or foolishly) sent 5 companies of Griffin's Battalion back to Fort Worth and only Lt. Joseph Chasteen's Co. F was still in Beaumont awaiting a train when September arrived.

William B.Franklin, commander of the initial invasion of Texas:

Union General Nathaniel Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, was making plans to attack Texas before turning his attention on his desired target of Mobile, AL. But the Abraham Lincoln administration wanted to first capture Texas with its plentiful cotton plantations and excellent beef ranches. Union interest in Texas resulted primarily from the need for cotton by northern textile mills. Banks earmarked 15,000 men for this campaign to capture Texas and placed them under the immediate command of General Franklin. Franklin loaded his troops on 18 transports in New Orleans and sailed for Sabine Pass on August 29, 1863, 5,000 soldiers and marines on board. The westward bound convoy was escorted by four heavily armed gunboats; the USS Clifton, USS Sachem, USS Arizona and USS Granite City. The Gunboats, mounting a total of eighteen guns, were under the command of Lt. Frederick Crocker, who had successfully captured Sabine Pass the previous October.

The USS Clifton was an 892-ton light-draft side-wheel gunboat, built in 1861 at Brooklyn, New York, as a civilian ferryboat. With the coming of the war, she was purchased by the US Navy and immediately converted into a gunboat.

Modern sketch of the USS Clifton:

Sketch of the USS Clifton by the boat’s doctor, Daniel D.T. Nestell:

USS Sachem was a screw steamer built in 1844 at New York City for use as a towing vessel in New York Harbor. She was also purchased by the Navy on September 20, 1861 and converted to a warship. Sachem was commanded by Acting Master Lemuel G. Crane and was one of two war vessels that escorted the USS Monitor to her historic engagement at Hampton Roads.

USS Arizona was a 950-ton iron side-wheel steamship built at Wilmington, Delaware, in 1859 for commercial employment. She was seized by the Confederates at New Orleans in January 1862 and placed in service as a blockade runner. On October 29, 1862, while bearing the name Caroline and attempting to run into Mobile, Alabama, she was captured in the Gulf of Mexico by USS Montgomery. Purchased from the prize court by the U.S. Navy in January 1863, she was commissioned as USS Arizona in early March and sent back to the Gulf of Mexico. On March 23, while en route to her new station, she captured a blockade-running schooner. Upon joining the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, Arizona was assigned to the forces fighting to control the waters west of the lower Mississippi River. She participated in the successful engagement with CSS Queen of the West on April 14, 1863 and the capture of Fort Burton, Louisiana, six days later. During May she took part in operations on the Red, Black and Ouachita Rivers. After that, she supported the campaign that took Port Hudson, LA in July, eliminating the final Confederate strong point on the Mississippi River.

A contemporary sketch showing in the middle top, left to right, the Clifton and Arizona in action against Fort Burton:

USS Granite City like Arizona had been a Confederate blockade runner. She was captured by the USS Tioga off Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas on March 22, 1863 while trying to disguise herself as a British vessel. She too was bought from the New York Prize Court for $55,000 and delivered to the Navy at New York on April 16, 1863. Acting Master Charles W. Lamson was placed in command and she was assigned to the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron, arriving in New Orleans two days before Franklin’s expedition left for Sabine Pass. Due to sickness on board, she was detained for a time in quarantine but departed on September 4th to join the rest of the Sabine Pass expedition.

Franklin and Banks’ plan was to arrive off Sabine Pass on September 6, sail up the Pass the next day and land in the vicinity of Sabine City. From there they would advance on Beaumont, seize the railroad and move overland to Houston and Galveston. The additional 10,000 men of the expedition would be brought from New Orleans once Beaumont was secured.

But problems began immediately. The scout boat sent ahead to mark the pass for the flottila, inexplicitly extinguished its signal lamp and abandoned its post outside Sabine Pass due to a rumor that the CSS Alabama was in their vicinity. The flotilla then sailed past Sabine Pass and by the time the error was caught, they had lost a day and did not arrive until September 7. The poorly executed Union rendezvous at the mouth of Sabine Pass was further compromised when the steering lights of the vessels were observed that night by the Confederates on shore. Surprise was lost.

The only Confederate defenders to see the signal lights from Fort Griffin that night were members of Captain Frederick Odlum’s Company F of the First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment, known as the “Davis Guards.” Odlum was in Sabine City as area commander that night and command of the company and Ft. Griffin had fallen to his niece’s husband and second in command, First Lieutenant Richard William “Dick” Dowling.

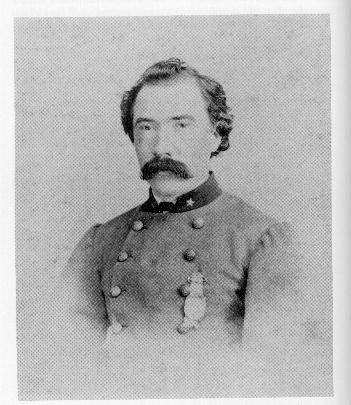

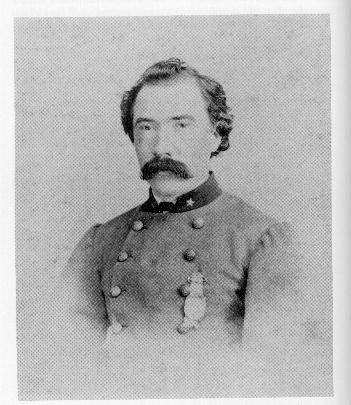

Photograph of Dick Dowling near the end of the war wearing his “Davis Guard” Medal:

Dowling was born in Tuam, County Galway, Ireland in 1838 and migrated with his parents to the United States in 1846. In 1846, the Dowling (originally O'Dowling ) family, fled Ireland’s Potato famine with its starvation, and poverty. Hoping for a better life, they sailed for America and took up residence in New Orleans. In 1853, a yellow fever epidemic claimed Dowling's mother and father leaving him an orphan at age 15. Four of the five Dowling children moved to Texas settling around Houston in 1855. By age 19, Dowling had grown into a handsome and charismatic young man. Dowling was described as a likable red-headed Irishman and wore a large mustache. In November 1857 he married the very beautiful Elizabeth Ann Odlum. They would have five children, but only two survived childhood: Mary Annie Dowling Robertson and Felize Sabine Dowling (who later went by the name Richard Dowling.) He opened a two-story saloon and billiards parlor on Houston’s Main Street called “The Shades.” Due to progressive business practices, it was wildly successful. In 1860, he sold his interests in it, invested in a Galveston liquor importing business and opened the "Bank of Bacchus" saloon on Houston’s Courthouse Square. "The Bank" as it was known locally, became Houston's most popular social gathering place in the 1860's and was renowned for its hospitality. He also operated an informal finance and pawn brokerage on the premises, cashing checks and making loans. His success with the loan business allowed him buy a third public house, "Hudgepeth's Bathing Saloon."

Dowling often tended bar at his various establishments and enjoyed inventing new cocktails. He was jovial and popular and was well respected in the community. He held membership in several civic organizations and a Houston volunteer fire company. In 1859, he joined a local militia company, the Houston Light Artillery. When this unit disbanded in 1860, many of its members organized another unit the “Davis Guards,” named in honor of then Senator Jefferson Davis. The unit was comprised mainly of Irish dockworkers.

With the secession of Texas in February 1861, the "Davis Guard" was mustered into Confederate service as an independent infantry company. It was commanded by Odlum and Dowling was the first lieutenant. Initially they were assigned to Galveston under the command of Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford but they were transferred in early March to Brownsville to take over the abandoned federal outposts on the Mexican Border. During this time, disputes broke out between Ford and Odlum over the treatment of his men. Amid claims of discrimination against Irish-Catholics, the “Davis Guard” was returned to Houston in late March of 1861.

In October of 1861, the Guard was assigned to Company F, Third Texas Artillery Battalion and manned big seacoast guns around Galveston. A year later they were reassigned as Company F, First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment and were trained as heavy artillerists by Colonel Joseph J. Cook. The Irish volunteers learned their lessons well, becoming crack artillerists.

Galveston was captured by the Federals in late 1862 so on the first day of 1863, Dowling and the “Davis Guards” were designated as the first wave in an assault on the Forty-second Massachusetts Infantry and a four gun battery of the Second Vermont Artillery barricaded on Kuhn's Wharf during the Battle of Galveston. The Davis Guard waded out to the wharf under heavy fire, but the attack was unsuccessful because their scaling ladders were too short. There were four casualties, including one fatality but the Confederates were still able to recapture the city.

After that, the Davis Guard was sent to Sabine Pass. On January 21, they were was ordered to serve as gunners on board two cotton-clad steamers sent to attack the two Federal blockaders that stood watch outside the pass. Dowling and a picked crew manned an 8-inch Columbiad on board the CSS Josiah H. Bell as it steamed out accompanied by the cotton clad steamer CSS Uncle Ben. A twenty mile running artillery duel ensued, ending with the capture of the USS Velocity, the USS Morning Light and their cargoes of much needed supplies.

The Davis Guard spent the next several months improving the fortifications at Fort Griffin and at drill. Using the antiquated armaments at the fort, they still became so proficient, that their fire could dominate the entire two- thousand yard width of the pass. Using the staked flags Kellersberg had placed in the pass as aiming points, they could nearly always hit their mark with the first shell. All this drill would soon payoff.

At daylight on the morning of Sept. 8, Capt. Odlum sailed down to the fort on board the gunboat Uncle Ben, after surveying the scene he told Dowling that he could spike the guns and retreat if he so chose. Dowling chose to remain. He would command Kellersberg’s pair of buried iron 32-pounders due to their longer range and he asked Confederate Surgeon George H. Bailey and Confederate engineer Lt. Nicholas H. Smith to command the two 24-pound iron guns and the 32-pound brass howitzers, repectively, although neither man had any artillery experience.

Shortly afterward, the four Union gunboats entered the Pass and fired about 20 shells at the fort without receiving any return fire. Many of the rifled cannons on the Union gunboats had 9-inch bores and fired 135-pound shells a distance of up to 3 miles. Because no return fire was forthcoming, Lt. Crocker became half assured that the fort was deserted. About mid-morning, the Uncle Ben steamed down past the fort in a daring run at the fleet. Crocker fired three shells at the gunboat, all of which passed over the Uncle Ben. The Uncle Ben then retreated into Sabine Lake, since its tiny 4" and 12-pound guns were no match for the Union fleet's firepower.

When the sound of cannon fire was heard by Lt. Chasteen in Beaumont at daylight on Sept. 8, he placed his infantry company aboard the steamer Roebuck and started for Sabine Pass.

During most of the day, Dowling kept all of his men out of sight in the bomb proofs under the fort, although each gun had been primed and loaded and a good supply of powder and cannon balls lay stashed beside each gun. During that time, only Dowling remained above ground with his small telescope. At about 2:30 p.m., he saw black smoke pour out of the invaders' smokestacks as the Union gunboats fired up their boilers for a closer attack on the fort. Dowling ordered each of his men above ground and the aim of each of the six Confederate guns was trained on Kellersberg’s 1,200-yard markers in the oyster reefs.

Map of the Battle:

Finally at 3:40 P.M. the Union gunboats began their advance through the pass, firing on the fort as they steamed forward. The Sachem led the advance up the Louisiana channel on the east side of the oyster reefs followed by the Granite City. The Clifton was a little behind it in the Texas channel followed by the Arizona. The lead gunboats continued to fire at the fort, but Dowling allowed no return fire as long as the boats were out of range. As soon as the Sachem passed the 1,200-yard marker, the fire of all six guns were concentrated on her. Either the third or fourth round, accounts vary, from one of the once buried 32-pounder, aimed by gunner Michael McKernan, pierced the Sachem's steam boiler and exploded. Immediately the Sachem's was shrouded in a cloud of steam as most of the crewmen and soldiers, some of them burned to the bone, jumped overboard. This left the gunboat without power in the channel near the Louisiana shore. The Arizona was forced to back up because it could not pass the Sachem and withdrew from the action.

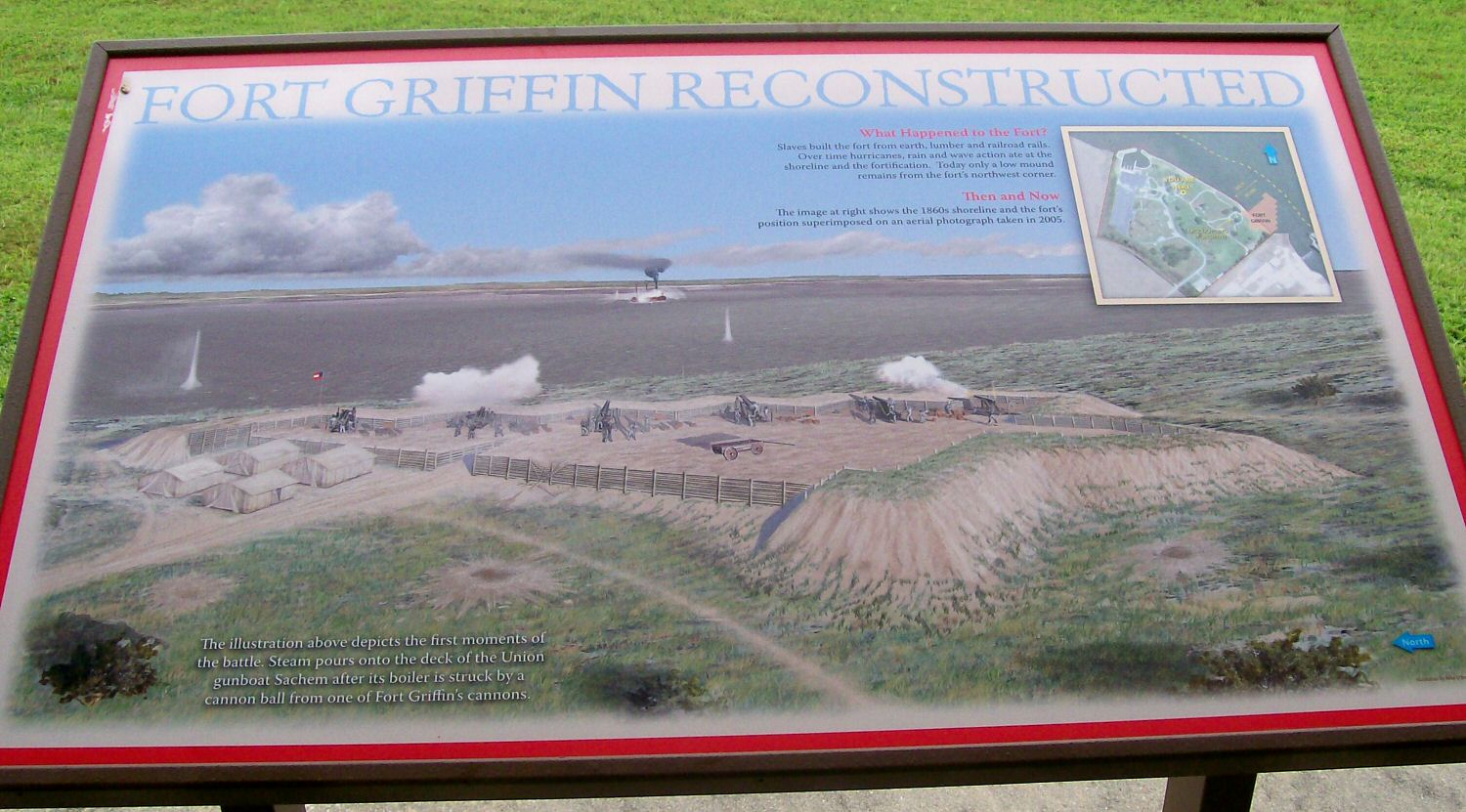

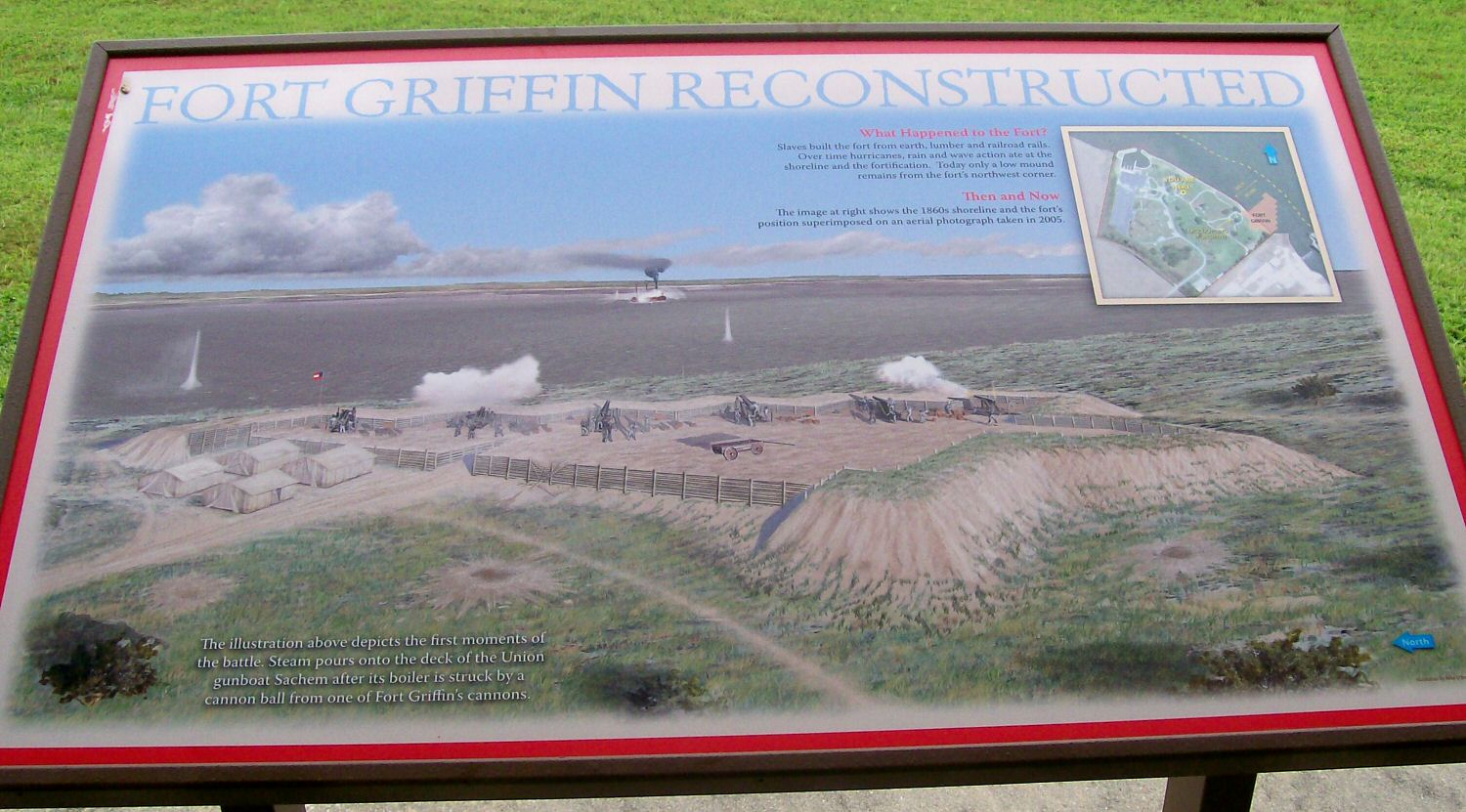

Site of Fort Griffin today, much of the fort is now underwater, since the pass was dredged when the Intercoastal Waterway was created. The dredging widen the pass, destroying the fort and eliminated the oyster bed in the middle of the channel that so befuddled the Union navy:

One of Dowling’s 24-pounders ran off its platform after these early shots and was out of action for the rest of the engagement. Dowling himself nearly became the only Confederate casualty of the engagement, when a Union cannon ball knocked the elevating screw from one of the iron 32-pounders after Dowling had just aimed the piece.

A modern painting of what the fort may have looked like:

The Clifton, which also carried several sharpshooters topside, pressed on up the Texas Channel. Dowling turned the fort’s five guns on her. Soon a shot from the fort cut away Clifton’s tiller rope as the range closed to a quarter of a mile. That left the gunboat without the ability to steer and caused it to run aground, however, the crew continued to exchange fire with the Confederate gunners. One Rebel cannon ball went bouncing down the Clifton's deck and cut off the head of the Clifton's starboard gunner. Another well-aimed projectile into the boiler sent steam and smoke throughout the vessel and forced the soldier, sailors and marines on board to abandon ship. With heavy casualties and no possibility of saving his ship, Lt. Crocker, ordered her Parrott gun spiked; her magazine flooded, and her signal book and spy glass destroyed. He then had her flag hauled down and a white flag hoisted. In just 40 minutes, both Sachem and Clifton lay helpless wrecks, aground and engulfed in steam from their ruptured boilers. The Granite City had no choice but to turn back, rather than face the accurate artillery of the fort.

Disabling of the USS Clifton:

In the confusion, the transports Suffolk and Continental collided while fleeing but sustained very little damage. Some of the transports became stuck on the outer bar and to lighten their loads 200 horses and mules were thrown overboard along with 200,000 rations, 50 wagons, and many kegs of gunpowder, barrels of corn meal and flour. Even the remaining gunboats, Arizona and Granite City ran aground on the outer bar but they were eventually able to extricate themselves, ending the battle.

The Davis Guards had fired their cannon 107 times in thirty-five minutes of action, a rate of less than two minutes per shot, which ranks far more rapid than the standard for heavy artillery. The Confederates captured 300 Union prisoners and two gunboats. Franklin was forced to turn back to New Orleans. The “Davis Guards” suffered no casualties during the battle.

As soon as Crocker raised a white flag, Dowling had a dilemma. He had only 47 Confederates in the fort, worn out from the reloading and firing the cannons. Two Confederate guns were knocked out during the battle. Dowling ran down to the Clifton and accept Crocker's sword and surrender. But he dared not expose the fact that there were only 47 men to accept the surrender of 350 prisoners, who might easily have overpowered their captors. Fortunately at 4 p.m., the Roebuck arrived from Beaumont, carrying Chasteen’s company of infantry and the additional Confederates made it possible to secure the capture of so many prisoners. After the battle the Uncle Ben pulled up to the Sachem and towed the gunboat to Sabine City.

At 5 o'clock A. M. that morning of September 8, Maj. Kellersberg received a telegram at his Galveston home that the Federal fleet was off Sabine Pass and that he should report immediately to Houston. He commandeered a hand car and with the aid of four slaves, covered the 48 miles of track to Houston in time to leave with General Magruder's staff on a train for Sabine City. En route, his fears remained that the repaired gun barrels may have exploded in the ensuing battle. However, his fears proved to be groundless.

Official Report of the Battle from Lt. Dowling to Capt. Odlum:

The Sabine Pass Lighthouse that Dowling described in his official report was built in 1854 and the light was first lit in 1856. During the Civil War, the light was extinguished by order of the Confederate Army to cause problems for Union troops attempting to attack the pass. The lighthouse did become the site of several Civil War skirmishes and Union soldiers used the tower to spy on enemy ships. After the war, the light was re-lit. The structure would survive a storm in 1886 that produced eight-foot tides, and a hurricane in 1915 before a decision was made in early 1952 to extinguish the light a final time after 95 years in service. Today the lighthouse is owned by the Cameron Preservation Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Cameron Parish. The lighthouse survived Hurricane Rita last year.

Sabine Pass Lighthouse the only manmade structure left in the pass that was there when the battle occurred:

Civil War era cupola of the lighthouse in Sabine Pass’s city park:

The next day being quite hot, Confederate soldiers buried the 50 or so dead soldiers, marines and sailors in a mass grave at Mesquite Point on Sabine Lake. It was a difficult and sickening chore, because the dead men were so badly scalded that the flesh fell from the bones. According to Lt. Chasteen, “One Negro was so white that you would never know that he was black, only for a piece of scalp showing his hair." The most visible and unusual victim was the starboard gunner of the Clifton, whose body had no head.

The Confederates at Sabine Pass had hardly had time to savor and appreciate their victory, but others quickly did, as the story of the "Alamo in reverse" was carried back to Houston and Galveston and eventually back to the Confederate Congress in Richmond. The congress quickly ordered that a special Davis Guard medal be cast for each of the men in the fort. This medal was the only honor of its kind known to have been bestowed on Confederate soldiers during the war. The Davis Guard medal was fashioned from a Mexican silver peso, each side smoothed off and engraved. The obverse side was inscribed in three lines, Sabine Pass / Sept 8th / 1863. In honor of the company's Irish heritage, a kelly green ribbon was attached to the suspension loop. According to the October 12, 1863, Houston Daily and Tri-Weekly Telegraph, grateful citizens of Dowling's home town of Houston raised money to fund the manufacture of the silver medals. For the officers, a similar medal was cast in gold, for which Houston ladies contributed their jewelry and men their watch cases to provide material and funds. On the 8th of September, 1864, the first anniversary of the battle, the ladies of Houston presented a medal to each member of the Davis Guard.

Davis Guard Medal. This medal is one of the most sought after Civil War relics. The one belonging to John W. White was at an auction house last year and was offered for sale at $35,000.00:

The battle had saved Texas from Union occupation until the end of the war and allowed East Texas to continue shipping cotton through the blockade and to act as the bread basket for Confederates fighting in Louisiana.

On October 17, Sachem was repaired and set sail for Orange, TX. She operated under the Texas Marine Department supporting the Confederate, Army on the Neches and Sabine Rivers. In March 1864, Sachem was back at Sabine Pass and, in April, was in Galveston under the command of a noted blockade runner, named John Davisson. She was reportedly laden with cotton and awaiting a chance to slip through the blockade. However, no further record of her career has ever been found.

Clifton also entered Confederate service with the Texas Marine Department, as a gunboat for some months. On March 21, 1864, she ran aground off Sabine Pass with 500 bales of cotton on board while attempting to run the blockade. After attempts to refloat her failed, Clifton was burned by her crew to prevent capture by Federal warships. Its smokestack remained visible until June 1957, when Hurricane Audrey washed the remaining wreckage away. Before it was swept away, the walking beam that worked the boat's engine, was recovered and put on display in Beaumont’s Riverfront Park where it still is today.

Walking Beam from Clifton in Beaumont’s Riverfront Park:

Granite City escaped capture that day but she was recaptured by Confederates on May 6, 1864 at Calcasieu Pass, La. She became a blockade runner but that is all that is known about her fate.

Arizona spent the rest of her service blockading the Texas coast with occasional operations on the Mississippi River and its tributaries. While steaming up the Mississippi enroute to New Orleans on February 27, 1865, she was accidentally destroyed by fire.

Within a short time, Lt. Dick Dowling was promoted to major and elevated to hero status. He was placed in command of all Houston recruitment. After the war, Dowling returned to his saloon business in Houston and quickly became one of the city's leading businessmen. The “Bank of Bacchus” again became one of the favorite meeting places for veterans of the war. Despite hard times in the south, Dowling’s ventures flourished. By 1867, he had expanded into Houston real estate, South Texas farm land, a bonded warehouse in Galveston, a construction company, a Trinity River steamboat, and oil and gas leases in three counties.

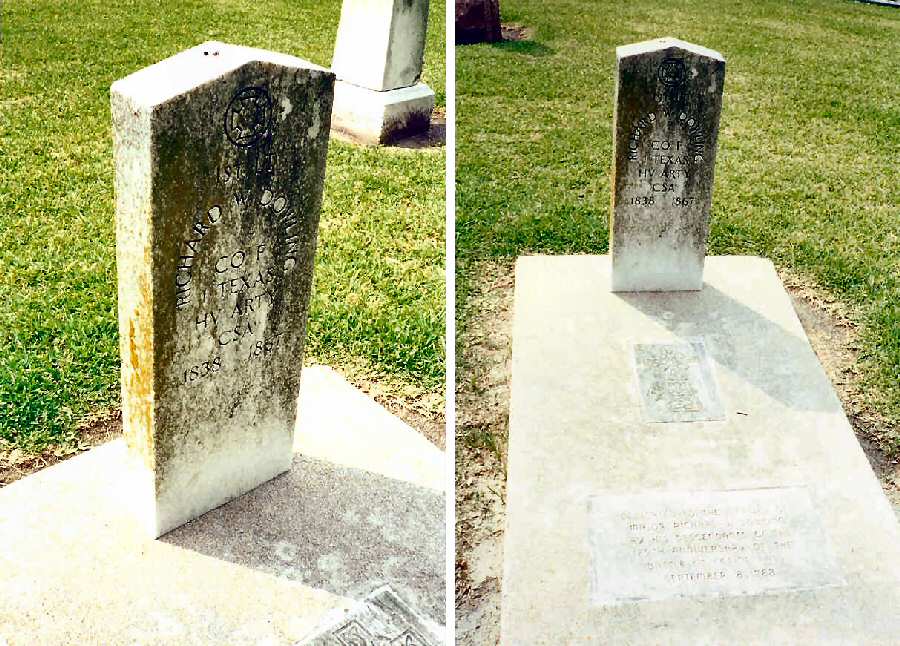

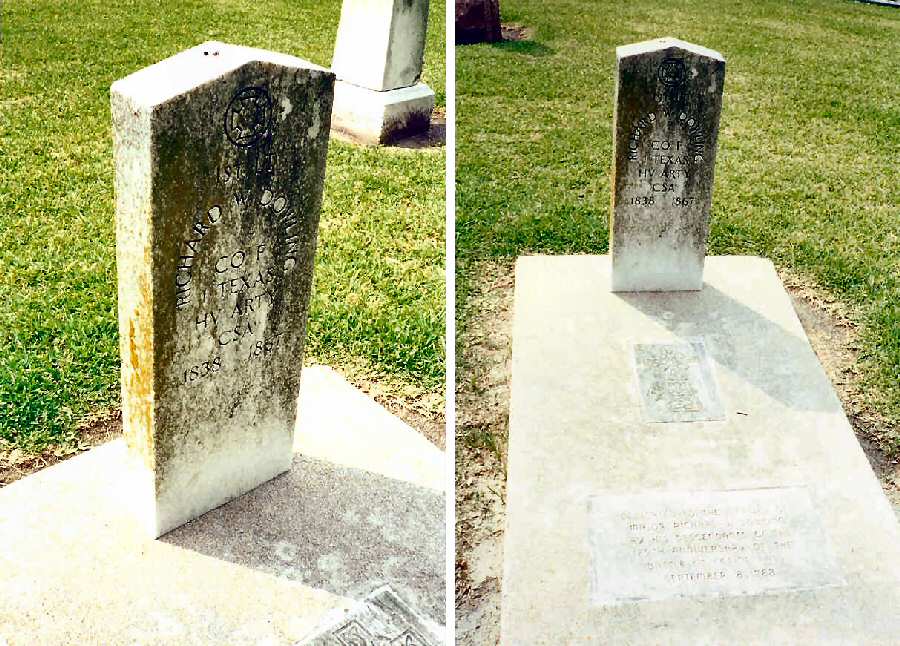

Dowling's promising future was cut short by the great yellow fever epidemic of 1867, which killed 3,000 people in Harris and Galveston counties. Dowling died on September 23, 1867 at age thirty. About half of the Sabine Pass veterans fell victim to the "yellowjack," that year after surviving the Battle at Sabine Pass unscathed. His Houston Hook and Ladder Company carried him to his final resting place in St. Vincent’s Cemetery while a soft rain fell and thousands of hushed Texans lined the streets for Houston’s first prominent celebrity.

Grave of Dick Dowling in the cemetery of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe Roman Catholic Church in Houston's Fifth Ward (formerly St. Vincent’s Parish). This area of Houston has always been an entry point for immigrants. The parish once was heavily Irish, later Mexican, Southeast Asian and now African (Nigerian):

Monument at Sabine Pass Battleground Park created by Beaumont sculptor Herring Coe during the Texas Centennial in 1936. The fanciful depiction has Dowling gazing into the pass he defended with his men. Today the park is closed indefinitely due to damage caused by Hurricane Rita last year, although the boat ramps reopened a couple of months ago:

Jefferson Davis compared the battle to the famous Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. where the Spartans under Leonidas had given their lives defending the critical pass, delaying the seemingly unstoppable advance of Xerxes and his massive Persian horde into the heartland of Greece. In his history of the Confederacy, Davis approvingly described the exploits of Dowling and his men at Sabine Pass, characterizing them as "marvelous" and stating, “there is no parallel in ancient or modern warfare to the victory of Dowling and his men at Sabine Pass considering the great odds against which they had to contend." Francis Lubbock, the former wartime governor of Texas, echoed Davis's assessment in his memoirs, describing the battle as "one of the most remarkable engagements of the war, resulting in a victory for the Confederate arms that immortalized those who participated in it."

The city of Houston erected a statue of Dowling on the grounds of its city hall. When the city hall was moved to a newer building in the early 20th century the statue was relocated to Hermann Park, near the monument to Sam Houston, where it remains today. Considering his Confederate ties, Dowling has a local legacy in Houston as the namesake of Dowling Street, a major artery of the city's predominantly African-American Third Ward and Dowling Middle School, which serves the city's predominantly African-American and Hispanic south.

Statue to Dowling in Hermann Park in Houston:

Men of the Davis Guards who fought at Sabine Pass:

2nd LT. N.H. Smith

Dr. Geo. H. Bailey

Michael Carr

Pat Clair

Thos. Daugherty

Michael Delaney

JNO. Drummond

Pat Fitzgerald

John Flood

Tom Haggerty

John Hassett

James Higgins

Tim Hurley

Pat Malone

Pat McDonnell

John McGrath

Michael McKernan

JNO. McNealis

Peter O'Hara

Maurice Powers

Charles Rheins

Pat Sullivan

Mathew Walsh

John W. White

Patrick Abbott

Abner R. Carter

James Corcoran

Hugh Deagan

Dan Donovan

Michael Eagan

James Flemming

William Gleason

William Hardy

John Hennessey

Tim Huggins

William L. Jett

Ally McCabe

Tim McDonough

John McKeever

Dan McMurray

Michael Monoghan

Lawrence Plunkett

Edw. Pritchard

Michael Sullivan

Thomas Sullivan

John T. Westley

Joseph Wilson

1LT Richard “Dick” Dowling

[This message has been edited by BQ78 (edited 9/8/2008 11:49a).]

Battle of Sabine Pass as portrayed in Harper’s Weekly:

In the spring of 1863, the Confederate chief engineer for East Texas, Major Julius Kellersberg, arrived at Sabine City with orders to construct Fort Griffin to guard Sabine Pass from a potential Yankee invasion. Upon arrival, he found the village largely deserted. Its two sawmills, railway station, roundhouse, many residences and supply of sawed lumber had been burned the previous October by Federal naval forces who had briefly occupied the town, until malaria drove them away.

Civil War Map of Sabine Pass:

Kellersberg looked at a previous fort built in the pass, Ft. Sabine and dismissed its location and construction immediately (it had also been dismantled by the U.S. Navy to a certain extent). For a new redoubt site, Kellersberg chose a point where the ship channel made a sharp right turn. This location would permit the new mud fort's guns to traverse across a broader arc of about 270 degrees. He brought with him from Houston a work force of about 500 conscripted slaves and a staff of Confederate engineers. For construction material, there was a supply of saw logs, crossties, railroad iron, and oyster shell, but no armament or munitions. Fort Sabine had been at the point where the Sabine channel split into the Texas and Louisiana channels, divided as it was by a shallow oyster shell reef that obstructed the middle passage. The new fort would be constructed where the channels exited a mile farther north.

The only artillery available were two old field guns, of 6-pound and 12-pound size, left over from the Mexican War and much too small for coastal defense against invading Union warships. Kellersberg directed that two 24-pound long iron guns mounted at Fort Grigsby near Port Neches, Tx. and another pair of 32-pound brass howitzers at a fort on the Sabine River, 12 miles south of Orange be transferred to Sabine Pass.

One day during the construction, an old fisherman told Kellersberg about two 32-pound iron guns that had been buried a year earlier when Fort Sabine had been abandoned. The engineer had seen these cannons during an inspection the previous year but knew as well that they had been spiked before the fort was abandoned. He feared that they had been damaged beyond repair, and was also aware that if his new installation were to be defended properly, he must acquire larger weapons, although he knew that none were available at that moment.

Together the fisherman and Kellersberg went to the site of the old fort and the fisherman showed the engineer the place where the guns were buried. After some probing, they located the buried weapons as well as a large supply of 32-pound solid shot cannon balls. As he had feared, the damage to the guns was considerable. Each had been spiked with round files; the trunnions (swivels) had been cut away and one barrel had been wedged with a cannon ball. Since Kellersberg had previously interspersed wooden dummies ('quakers') with real artillery among Galveston's beach defenses, Kellersberg was reluctant to throw these damaged pieces away. At the first opportunity, he took them to the Confederate foundry in Galveston.

At home in Galveston, his chief, Col. Valery Sulakowski, a veteran of the Austrian Army and the organizer of the 1st Texas Rocket Battery (that’s a story for another day) advised strongly against trying to repair the rusted weapons. Still reluctant to dispose of them, Kellersberg consulted the local foundry's chief machinist. The foundryman attacked the problem with tremendous vigor. Day and night, he and Kellersberg hurried to complete the repairs, becasue already reports had reached Gen. John Bankhead “Prince John” Magruder's headquarters in Houston that the Federals were expected to turn their attention to the Texas coast.

“Prince John” Magruder, Confederate Commander of the Department of East Texas:

Repairs to the big guns required molding special 16-inch iron rings and stretching them over the barrels while they were heated and still glowing red. Then a groove one-half inch deep and one and one-half inches wide was twisted into each barrel over which each of the threaded wrought iron rings was stretched. The greatest hazard lay in boring the grooves too deep, which might weaken the barrels' ability to withstand the concussion, causing them to explode when fired.

Shortly afterward, Major Kellersberg loaded the repaired cannons along with a supply of shells and solid shot on the train bound for Beaumont. While en route to Sabine City, he gave each gun two coats of paint in order to save time. Two days later, the smoothbore weapons were mounted on gun carriages in Fort Griffin and placed in firing position on the fort's parapets along its sawtooth front. The cannons survived test firings and Kellersberg drove white markers near the end of the Texas and Louisiana channels on each side of the oyster reef to indicate the guns' maximum range.

When the engineer returned to Galveston, his fears were not dimmed completely and he recorded in his German-language memoirs that he spent many sleepless nights afterward worried about how these guns might perform.

At the same time Kellersberg was building Fort Griffin in Sabine Pass in May, 1863, Magruder began a systematic reduction of Confederate forces at Sabine Pass even though he felt an attack was imminent. Several companies of Spaight's Battalion were transferred to Opelousas, La., where General William B. Franklin was leading a Union invasion up the Bayou Teche. Initially Magruder sent Col. William F. Griffin (for whom the fort was named) and his battalion from Galveston to Sabine Pass. But when Comanche Indians began attacking the homes of Griffin's soldiers, west of Fort Worth during the early summer, the battalion threatened to desert or mutiny unless they were sent back to Tarrant County to subdue the Indians. Magruder reluctantly (or foolishly) sent 5 companies of Griffin's Battalion back to Fort Worth and only Lt. Joseph Chasteen's Co. F was still in Beaumont awaiting a train when September arrived.

William B.Franklin, commander of the initial invasion of Texas:

Union General Nathaniel Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, was making plans to attack Texas before turning his attention on his desired target of Mobile, AL. But the Abraham Lincoln administration wanted to first capture Texas with its plentiful cotton plantations and excellent beef ranches. Union interest in Texas resulted primarily from the need for cotton by northern textile mills. Banks earmarked 15,000 men for this campaign to capture Texas and placed them under the immediate command of General Franklin. Franklin loaded his troops on 18 transports in New Orleans and sailed for Sabine Pass on August 29, 1863, 5,000 soldiers and marines on board. The westward bound convoy was escorted by four heavily armed gunboats; the USS Clifton, USS Sachem, USS Arizona and USS Granite City. The Gunboats, mounting a total of eighteen guns, were under the command of Lt. Frederick Crocker, who had successfully captured Sabine Pass the previous October.

The USS Clifton was an 892-ton light-draft side-wheel gunboat, built in 1861 at Brooklyn, New York, as a civilian ferryboat. With the coming of the war, she was purchased by the US Navy and immediately converted into a gunboat.

Modern sketch of the USS Clifton:

Sketch of the USS Clifton by the boat’s doctor, Daniel D.T. Nestell:

USS Sachem was a screw steamer built in 1844 at New York City for use as a towing vessel in New York Harbor. She was also purchased by the Navy on September 20, 1861 and converted to a warship. Sachem was commanded by Acting Master Lemuel G. Crane and was one of two war vessels that escorted the USS Monitor to her historic engagement at Hampton Roads.

USS Arizona was a 950-ton iron side-wheel steamship built at Wilmington, Delaware, in 1859 for commercial employment. She was seized by the Confederates at New Orleans in January 1862 and placed in service as a blockade runner. On October 29, 1862, while bearing the name Caroline and attempting to run into Mobile, Alabama, she was captured in the Gulf of Mexico by USS Montgomery. Purchased from the prize court by the U.S. Navy in January 1863, she was commissioned as USS Arizona in early March and sent back to the Gulf of Mexico. On March 23, while en route to her new station, she captured a blockade-running schooner. Upon joining the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, Arizona was assigned to the forces fighting to control the waters west of the lower Mississippi River. She participated in the successful engagement with CSS Queen of the West on April 14, 1863 and the capture of Fort Burton, Louisiana, six days later. During May she took part in operations on the Red, Black and Ouachita Rivers. After that, she supported the campaign that took Port Hudson, LA in July, eliminating the final Confederate strong point on the Mississippi River.

A contemporary sketch showing in the middle top, left to right, the Clifton and Arizona in action against Fort Burton:

USS Granite City like Arizona had been a Confederate blockade runner. She was captured by the USS Tioga off Eleuthera Island in the Bahamas on March 22, 1863 while trying to disguise herself as a British vessel. She too was bought from the New York Prize Court for $55,000 and delivered to the Navy at New York on April 16, 1863. Acting Master Charles W. Lamson was placed in command and she was assigned to the Western Gulf Blockading Squadron, arriving in New Orleans two days before Franklin’s expedition left for Sabine Pass. Due to sickness on board, she was detained for a time in quarantine but departed on September 4th to join the rest of the Sabine Pass expedition.

Franklin and Banks’ plan was to arrive off Sabine Pass on September 6, sail up the Pass the next day and land in the vicinity of Sabine City. From there they would advance on Beaumont, seize the railroad and move overland to Houston and Galveston. The additional 10,000 men of the expedition would be brought from New Orleans once Beaumont was secured.

But problems began immediately. The scout boat sent ahead to mark the pass for the flottila, inexplicitly extinguished its signal lamp and abandoned its post outside Sabine Pass due to a rumor that the CSS Alabama was in their vicinity. The flotilla then sailed past Sabine Pass and by the time the error was caught, they had lost a day and did not arrive until September 7. The poorly executed Union rendezvous at the mouth of Sabine Pass was further compromised when the steering lights of the vessels were observed that night by the Confederates on shore. Surprise was lost.

The only Confederate defenders to see the signal lights from Fort Griffin that night were members of Captain Frederick Odlum’s Company F of the First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment, known as the “Davis Guards.” Odlum was in Sabine City as area commander that night and command of the company and Ft. Griffin had fallen to his niece’s husband and second in command, First Lieutenant Richard William “Dick” Dowling.

Photograph of Dick Dowling near the end of the war wearing his “Davis Guard” Medal:

Dowling was born in Tuam, County Galway, Ireland in 1838 and migrated with his parents to the United States in 1846. In 1846, the Dowling (originally O'Dowling ) family, fled Ireland’s Potato famine with its starvation, and poverty. Hoping for a better life, they sailed for America and took up residence in New Orleans. In 1853, a yellow fever epidemic claimed Dowling's mother and father leaving him an orphan at age 15. Four of the five Dowling children moved to Texas settling around Houston in 1855. By age 19, Dowling had grown into a handsome and charismatic young man. Dowling was described as a likable red-headed Irishman and wore a large mustache. In November 1857 he married the very beautiful Elizabeth Ann Odlum. They would have five children, but only two survived childhood: Mary Annie Dowling Robertson and Felize Sabine Dowling (who later went by the name Richard Dowling.) He opened a two-story saloon and billiards parlor on Houston’s Main Street called “The Shades.” Due to progressive business practices, it was wildly successful. In 1860, he sold his interests in it, invested in a Galveston liquor importing business and opened the "Bank of Bacchus" saloon on Houston’s Courthouse Square. "The Bank" as it was known locally, became Houston's most popular social gathering place in the 1860's and was renowned for its hospitality. He also operated an informal finance and pawn brokerage on the premises, cashing checks and making loans. His success with the loan business allowed him buy a third public house, "Hudgepeth's Bathing Saloon."

Dowling often tended bar at his various establishments and enjoyed inventing new cocktails. He was jovial and popular and was well respected in the community. He held membership in several civic organizations and a Houston volunteer fire company. In 1859, he joined a local militia company, the Houston Light Artillery. When this unit disbanded in 1860, many of its members organized another unit the “Davis Guards,” named in honor of then Senator Jefferson Davis. The unit was comprised mainly of Irish dockworkers.

With the secession of Texas in February 1861, the "Davis Guard" was mustered into Confederate service as an independent infantry company. It was commanded by Odlum and Dowling was the first lieutenant. Initially they were assigned to Galveston under the command of Colonel John S. "Rip" Ford but they were transferred in early March to Brownsville to take over the abandoned federal outposts on the Mexican Border. During this time, disputes broke out between Ford and Odlum over the treatment of his men. Amid claims of discrimination against Irish-Catholics, the “Davis Guard” was returned to Houston in late March of 1861.

In October of 1861, the Guard was assigned to Company F, Third Texas Artillery Battalion and manned big seacoast guns around Galveston. A year later they were reassigned as Company F, First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment and were trained as heavy artillerists by Colonel Joseph J. Cook. The Irish volunteers learned their lessons well, becoming crack artillerists.

Galveston was captured by the Federals in late 1862 so on the first day of 1863, Dowling and the “Davis Guards” were designated as the first wave in an assault on the Forty-second Massachusetts Infantry and a four gun battery of the Second Vermont Artillery barricaded on Kuhn's Wharf during the Battle of Galveston. The Davis Guard waded out to the wharf under heavy fire, but the attack was unsuccessful because their scaling ladders were too short. There were four casualties, including one fatality but the Confederates were still able to recapture the city.

After that, the Davis Guard was sent to Sabine Pass. On January 21, they were was ordered to serve as gunners on board two cotton-clad steamers sent to attack the two Federal blockaders that stood watch outside the pass. Dowling and a picked crew manned an 8-inch Columbiad on board the CSS Josiah H. Bell as it steamed out accompanied by the cotton clad steamer CSS Uncle Ben. A twenty mile running artillery duel ensued, ending with the capture of the USS Velocity, the USS Morning Light and their cargoes of much needed supplies.

The Davis Guard spent the next several months improving the fortifications at Fort Griffin and at drill. Using the antiquated armaments at the fort, they still became so proficient, that their fire could dominate the entire two- thousand yard width of the pass. Using the staked flags Kellersberg had placed in the pass as aiming points, they could nearly always hit their mark with the first shell. All this drill would soon payoff.

At daylight on the morning of Sept. 8, Capt. Odlum sailed down to the fort on board the gunboat Uncle Ben, after surveying the scene he told Dowling that he could spike the guns and retreat if he so chose. Dowling chose to remain. He would command Kellersberg’s pair of buried iron 32-pounders due to their longer range and he asked Confederate Surgeon George H. Bailey and Confederate engineer Lt. Nicholas H. Smith to command the two 24-pound iron guns and the 32-pound brass howitzers, repectively, although neither man had any artillery experience.

Shortly afterward, the four Union gunboats entered the Pass and fired about 20 shells at the fort without receiving any return fire. Many of the rifled cannons on the Union gunboats had 9-inch bores and fired 135-pound shells a distance of up to 3 miles. Because no return fire was forthcoming, Lt. Crocker became half assured that the fort was deserted. About mid-morning, the Uncle Ben steamed down past the fort in a daring run at the fleet. Crocker fired three shells at the gunboat, all of which passed over the Uncle Ben. The Uncle Ben then retreated into Sabine Lake, since its tiny 4" and 12-pound guns were no match for the Union fleet's firepower.

When the sound of cannon fire was heard by Lt. Chasteen in Beaumont at daylight on Sept. 8, he placed his infantry company aboard the steamer Roebuck and started for Sabine Pass.

During most of the day, Dowling kept all of his men out of sight in the bomb proofs under the fort, although each gun had been primed and loaded and a good supply of powder and cannon balls lay stashed beside each gun. During that time, only Dowling remained above ground with his small telescope. At about 2:30 p.m., he saw black smoke pour out of the invaders' smokestacks as the Union gunboats fired up their boilers for a closer attack on the fort. Dowling ordered each of his men above ground and the aim of each of the six Confederate guns was trained on Kellersberg’s 1,200-yard markers in the oyster reefs.

Map of the Battle:

Finally at 3:40 P.M. the Union gunboats began their advance through the pass, firing on the fort as they steamed forward. The Sachem led the advance up the Louisiana channel on the east side of the oyster reefs followed by the Granite City. The Clifton was a little behind it in the Texas channel followed by the Arizona. The lead gunboats continued to fire at the fort, but Dowling allowed no return fire as long as the boats were out of range. As soon as the Sachem passed the 1,200-yard marker, the fire of all six guns were concentrated on her. Either the third or fourth round, accounts vary, from one of the once buried 32-pounder, aimed by gunner Michael McKernan, pierced the Sachem's steam boiler and exploded. Immediately the Sachem's was shrouded in a cloud of steam as most of the crewmen and soldiers, some of them burned to the bone, jumped overboard. This left the gunboat without power in the channel near the Louisiana shore. The Arizona was forced to back up because it could not pass the Sachem and withdrew from the action.

Site of Fort Griffin today, much of the fort is now underwater, since the pass was dredged when the Intercoastal Waterway was created. The dredging widen the pass, destroying the fort and eliminated the oyster bed in the middle of the channel that so befuddled the Union navy:

One of Dowling’s 24-pounders ran off its platform after these early shots and was out of action for the rest of the engagement. Dowling himself nearly became the only Confederate casualty of the engagement, when a Union cannon ball knocked the elevating screw from one of the iron 32-pounders after Dowling had just aimed the piece.

A modern painting of what the fort may have looked like:

The Clifton, which also carried several sharpshooters topside, pressed on up the Texas Channel. Dowling turned the fort’s five guns on her. Soon a shot from the fort cut away Clifton’s tiller rope as the range closed to a quarter of a mile. That left the gunboat without the ability to steer and caused it to run aground, however, the crew continued to exchange fire with the Confederate gunners. One Rebel cannon ball went bouncing down the Clifton's deck and cut off the head of the Clifton's starboard gunner. Another well-aimed projectile into the boiler sent steam and smoke throughout the vessel and forced the soldier, sailors and marines on board to abandon ship. With heavy casualties and no possibility of saving his ship, Lt. Crocker, ordered her Parrott gun spiked; her magazine flooded, and her signal book and spy glass destroyed. He then had her flag hauled down and a white flag hoisted. In just 40 minutes, both Sachem and Clifton lay helpless wrecks, aground and engulfed in steam from their ruptured boilers. The Granite City had no choice but to turn back, rather than face the accurate artillery of the fort.

Disabling of the USS Clifton:

In the confusion, the transports Suffolk and Continental collided while fleeing but sustained very little damage. Some of the transports became stuck on the outer bar and to lighten their loads 200 horses and mules were thrown overboard along with 200,000 rations, 50 wagons, and many kegs of gunpowder, barrels of corn meal and flour. Even the remaining gunboats, Arizona and Granite City ran aground on the outer bar but they were eventually able to extricate themselves, ending the battle.

The Davis Guards had fired their cannon 107 times in thirty-five minutes of action, a rate of less than two minutes per shot, which ranks far more rapid than the standard for heavy artillery. The Confederates captured 300 Union prisoners and two gunboats. Franklin was forced to turn back to New Orleans. The “Davis Guards” suffered no casualties during the battle.

As soon as Crocker raised a white flag, Dowling had a dilemma. He had only 47 Confederates in the fort, worn out from the reloading and firing the cannons. Two Confederate guns were knocked out during the battle. Dowling ran down to the Clifton and accept Crocker's sword and surrender. But he dared not expose the fact that there were only 47 men to accept the surrender of 350 prisoners, who might easily have overpowered their captors. Fortunately at 4 p.m., the Roebuck arrived from Beaumont, carrying Chasteen’s company of infantry and the additional Confederates made it possible to secure the capture of so many prisoners. After the battle the Uncle Ben pulled up to the Sachem and towed the gunboat to Sabine City.

At 5 o'clock A. M. that morning of September 8, Maj. Kellersberg received a telegram at his Galveston home that the Federal fleet was off Sabine Pass and that he should report immediately to Houston. He commandeered a hand car and with the aid of four slaves, covered the 48 miles of track to Houston in time to leave with General Magruder's staff on a train for Sabine City. En route, his fears remained that the repaired gun barrels may have exploded in the ensuing battle. However, his fears proved to be groundless.

Official Report of the Battle from Lt. Dowling to Capt. Odlum:

quote:

CAPTAIN: On Monday morning, about 2 o'clock, the enemy were signaling, and fearing an Attack, l ordered all the guns at the fort manned, and remained in that position until daylight, when there were two steamers evidently sounding for the channel on the bar; a large frigate outside. During the evening they were re-enforced to the number of twenty-two vessels of different classes.

On the morning of the 8th, the U.S. gunboat Clifton anchored opposite the light-house, and fired twenty-six shell at the fort, all in excellent range, one shell landing on the works and another striking the south angle of the fort without doing any material damage. The firing commenced at 6:30 o'clock and finished at 7:30 o'clock when the C. S. gunboat Uncle Ben steamed down near the fort. The U. S. gunboat Sachem opened on her with a 30-pounder Parrott gun. She fired three shots which passed over the fort and missed the Ben. The whole fleet then drew off, and remained out of range until 3:40 o'clock, when the Sachem and Arizona steamed into line up the Louisiana channel, the Clifton and one boat, name unknown, remaining at the junction of the two channels. I allowed the two former boats to approach within 1,200 yds, when I opened fire with the whole of my battery on the Sachem which, after the third or fourth round, hoisted the white flag, one of the shots passing through her steam drum. The Clifton in the meantime had attempted to pass up through Texas Channel, but receiving a shot which carried away her tiller rope, she became unmanageable and grounded about 500 yds. below the fort which enabled me to concentrate all my guns on her, two 32-pounder smooth-bores; two 24-pounder smooth-bores and two 32-pounder howitzers. She withstood our fire some 25 or 35 minutes, when she also hoisted a white flag. During the time she was aground, she used grape, and her sharpshooters poured an incessant shower of Minie balls into the works. The fight lasted from the time I fired the first gun until the boats surrendered - about three-quarters of an hour. l immediately boarded the captured Clifton, to inspect her magazines, accompanied by one the ship's officers and discovered it safe and well stocked with ordnance stores. l did not visit the magazine of the Sachem, not having any small boat to board her with. The C. S. gunboat Uncle Ben steamed down to the Sachem and towed her into the wharf Her magazine was destroyed by the enemy flooding it.

I was nobly and gallantly assisted by Lt. N. H. Smith, of the Engineer Corps, who by his coolness and bravery won the respect and admiration of the whole command. Ass't. Surg. George H. Bailey, having nothing to do in his own line, nobly pulled off his coat and assisted in administering Magruder pills to the enemy, behaving with great coolness. During the engagement the works were visited by Capt. F. H. Odlum, commanding post; Maj. (Col. ) Leon Smith, commanding Marine Department of Texas. Capt. W. S. Good, ordnance officer, and Dr. Murray, acting ass't. surgeon, with great coolness and gallantry, enabled me to send re-enforcements, as the men were becoming exhausted by the rapidity of our fire; but before they could accomplish their mission, the enemy surrendered. Thus, it will be seen we captured with 47 men two gunboats, mounting thirteen guns of the heaviest caliber, and about 350 prisoners. All my men behaved like heroes; not a man flinched from his post. Our motto was "victory or death." I beg leave to make particular mention of Private M Michael McKernan, who, from his well-known capacity as a gunner, l assigned as gunner, and nobly did he do his duty. It was his shot struck the Sachem in her steam drum. Too much praise cannot be awarded Maj. (Col.) Leon Smith for his activity and energy in saving and bringing the vessel into port.

I have the honor, captain, to remain in your most obedient servant,

R. W. Dowling, 1st. Lt., Cook's Artillery.

The Sabine Pass Lighthouse that Dowling described in his official report was built in 1854 and the light was first lit in 1856. During the Civil War, the light was extinguished by order of the Confederate Army to cause problems for Union troops attempting to attack the pass. The lighthouse did become the site of several Civil War skirmishes and Union soldiers used the tower to spy on enemy ships. After the war, the light was re-lit. The structure would survive a storm in 1886 that produced eight-foot tides, and a hurricane in 1915 before a decision was made in early 1952 to extinguish the light a final time after 95 years in service. Today the lighthouse is owned by the Cameron Preservation Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Cameron Parish. The lighthouse survived Hurricane Rita last year.

Sabine Pass Lighthouse the only manmade structure left in the pass that was there when the battle occurred:

Civil War era cupola of the lighthouse in Sabine Pass’s city park:

The next day being quite hot, Confederate soldiers buried the 50 or so dead soldiers, marines and sailors in a mass grave at Mesquite Point on Sabine Lake. It was a difficult and sickening chore, because the dead men were so badly scalded that the flesh fell from the bones. According to Lt. Chasteen, “One Negro was so white that you would never know that he was black, only for a piece of scalp showing his hair." The most visible and unusual victim was the starboard gunner of the Clifton, whose body had no head.

The Confederates at Sabine Pass had hardly had time to savor and appreciate their victory, but others quickly did, as the story of the "Alamo in reverse" was carried back to Houston and Galveston and eventually back to the Confederate Congress in Richmond. The congress quickly ordered that a special Davis Guard medal be cast for each of the men in the fort. This medal was the only honor of its kind known to have been bestowed on Confederate soldiers during the war. The Davis Guard medal was fashioned from a Mexican silver peso, each side smoothed off and engraved. The obverse side was inscribed in three lines, Sabine Pass / Sept 8th / 1863. In honor of the company's Irish heritage, a kelly green ribbon was attached to the suspension loop. According to the October 12, 1863, Houston Daily and Tri-Weekly Telegraph, grateful citizens of Dowling's home town of Houston raised money to fund the manufacture of the silver medals. For the officers, a similar medal was cast in gold, for which Houston ladies contributed their jewelry and men their watch cases to provide material and funds. On the 8th of September, 1864, the first anniversary of the battle, the ladies of Houston presented a medal to each member of the Davis Guard.

Davis Guard Medal. This medal is one of the most sought after Civil War relics. The one belonging to John W. White was at an auction house last year and was offered for sale at $35,000.00:

The battle had saved Texas from Union occupation until the end of the war and allowed East Texas to continue shipping cotton through the blockade and to act as the bread basket for Confederates fighting in Louisiana.

On October 17, Sachem was repaired and set sail for Orange, TX. She operated under the Texas Marine Department supporting the Confederate, Army on the Neches and Sabine Rivers. In March 1864, Sachem was back at Sabine Pass and, in April, was in Galveston under the command of a noted blockade runner, named John Davisson. She was reportedly laden with cotton and awaiting a chance to slip through the blockade. However, no further record of her career has ever been found.

Clifton also entered Confederate service with the Texas Marine Department, as a gunboat for some months. On March 21, 1864, she ran aground off Sabine Pass with 500 bales of cotton on board while attempting to run the blockade. After attempts to refloat her failed, Clifton was burned by her crew to prevent capture by Federal warships. Its smokestack remained visible until June 1957, when Hurricane Audrey washed the remaining wreckage away. Before it was swept away, the walking beam that worked the boat's engine, was recovered and put on display in Beaumont’s Riverfront Park where it still is today.

Walking Beam from Clifton in Beaumont’s Riverfront Park:

Granite City escaped capture that day but she was recaptured by Confederates on May 6, 1864 at Calcasieu Pass, La. She became a blockade runner but that is all that is known about her fate.

Arizona spent the rest of her service blockading the Texas coast with occasional operations on the Mississippi River and its tributaries. While steaming up the Mississippi enroute to New Orleans on February 27, 1865, she was accidentally destroyed by fire.

Within a short time, Lt. Dick Dowling was promoted to major and elevated to hero status. He was placed in command of all Houston recruitment. After the war, Dowling returned to his saloon business in Houston and quickly became one of the city's leading businessmen. The “Bank of Bacchus” again became one of the favorite meeting places for veterans of the war. Despite hard times in the south, Dowling’s ventures flourished. By 1867, he had expanded into Houston real estate, South Texas farm land, a bonded warehouse in Galveston, a construction company, a Trinity River steamboat, and oil and gas leases in three counties.

Dowling's promising future was cut short by the great yellow fever epidemic of 1867, which killed 3,000 people in Harris and Galveston counties. Dowling died on September 23, 1867 at age thirty. About half of the Sabine Pass veterans fell victim to the "yellowjack," that year after surviving the Battle at Sabine Pass unscathed. His Houston Hook and Ladder Company carried him to his final resting place in St. Vincent’s Cemetery while a soft rain fell and thousands of hushed Texans lined the streets for Houston’s first prominent celebrity.

Grave of Dick Dowling in the cemetery of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe Roman Catholic Church in Houston's Fifth Ward (formerly St. Vincent’s Parish). This area of Houston has always been an entry point for immigrants. The parish once was heavily Irish, later Mexican, Southeast Asian and now African (Nigerian):

Monument at Sabine Pass Battleground Park created by Beaumont sculptor Herring Coe during the Texas Centennial in 1936. The fanciful depiction has Dowling gazing into the pass he defended with his men. Today the park is closed indefinitely due to damage caused by Hurricane Rita last year, although the boat ramps reopened a couple of months ago:

Jefferson Davis compared the battle to the famous Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. where the Spartans under Leonidas had given their lives defending the critical pass, delaying the seemingly unstoppable advance of Xerxes and his massive Persian horde into the heartland of Greece. In his history of the Confederacy, Davis approvingly described the exploits of Dowling and his men at Sabine Pass, characterizing them as "marvelous" and stating, “there is no parallel in ancient or modern warfare to the victory of Dowling and his men at Sabine Pass considering the great odds against which they had to contend." Francis Lubbock, the former wartime governor of Texas, echoed Davis's assessment in his memoirs, describing the battle as "one of the most remarkable engagements of the war, resulting in a victory for the Confederate arms that immortalized those who participated in it."

The city of Houston erected a statue of Dowling on the grounds of its city hall. When the city hall was moved to a newer building in the early 20th century the statue was relocated to Hermann Park, near the monument to Sam Houston, where it remains today. Considering his Confederate ties, Dowling has a local legacy in Houston as the namesake of Dowling Street, a major artery of the city's predominantly African-American Third Ward and Dowling Middle School, which serves the city's predominantly African-American and Hispanic south.

Statue to Dowling in Hermann Park in Houston:

Men of the Davis Guards who fought at Sabine Pass:

2nd LT. N.H. Smith

Dr. Geo. H. Bailey

Michael Carr

Pat Clair

Thos. Daugherty

Michael Delaney

JNO. Drummond

Pat Fitzgerald

John Flood

Tom Haggerty

John Hassett

James Higgins

Tim Hurley

Pat Malone

Pat McDonnell

John McGrath

Michael McKernan

JNO. McNealis

Peter O'Hara

Maurice Powers

Charles Rheins

Pat Sullivan

Mathew Walsh

John W. White

Patrick Abbott

Abner R. Carter

James Corcoran

Hugh Deagan

Dan Donovan

Michael Eagan

James Flemming

William Gleason

William Hardy

John Hennessey

Tim Huggins

William L. Jett

Ally McCabe

Tim McDonough

John McKeever

Dan McMurray

Michael Monoghan

Lawrence Plunkett

Edw. Pritchard

Michael Sullivan

Thomas Sullivan

John T. Westley

Joseph Wilson

1LT Richard “Dick” Dowling

[This message has been edited by BQ78 (edited 9/8/2008 11:49a).]