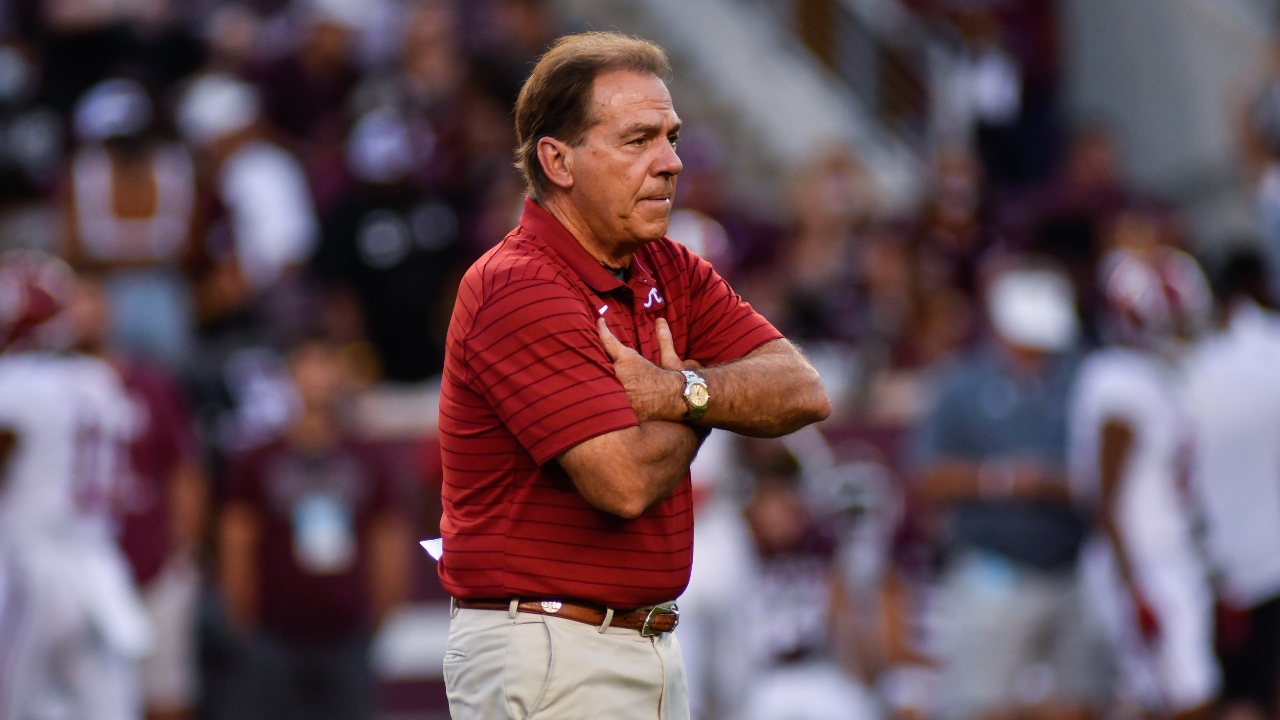

Saban dusts off crystal ball, detests NIL-created 'uneven playing field'

DESTIN, Fla. — A decade ago, Nick Saban warned us about a pandora’s box threatening to release a plague of curses upon college football.

Earlier this week at the Southeastern Conference Spring Meetings, the omnipotent Alabama deity reminded assembled media of his extraordinary foresight.

“I made the statement years ago — and I got very criticized for it — ‘Is this what we want college football to become?’” Saban recalled. “Now, it’s kind of becoming that. I don’t think it’s going to be a level playing field because some people are showing a willingness to spend more than others.”

That’s right. The soothsayer of college football foretold the unintended problems that NIL would bring.

Except, when he asked in 2013 “is this what we want college football to become,” he was referring to Johnny Manziel and fast-tempo offenses, not athletes’ fast-rising earning potential brought on by Name, Image and Likeness.

Clearly, Saban struggles with memory. Or does he just struggle with accuracy? Or the truth?

This time last year, Saban admitted to the spring meetings media he had no evidence to support his accusations that Texas A&M “bought its entire recruiting class.”

Of course, Saban made those statements while urging boosters to give larger financial donations, presumably so Alabama could buy its recruiting class.

He was at it again this week. While lamenting the “uneven playing field” in college football, Saban complained, “The way Southern Cal, Texas and Texas A&M are spending money … ‘It’s what are you willing to spend?”’

Oddly, two years ago, Saban bragged to Texas high school coaches in San Antonio that then-Crimson Tide quarterback Bryce Young had $1 million in deals merely weeks after NIL was approved.

Young’s deal equated to roughly 10 percent of what all Texas A&M athletes — male and female — in all sports have earned over the last two years. A&M Director of Athletics Ross Bjork said Aggies athletes have earned approximately $10 million in NIL deals.

“I don’t know what (Saban’s) referring to in terms of what dollar figures he has,” Bjork said, who acknowledged A&M has been embracing NIL.

“When somebody makes a comment to me, it’s hearsay,” Bjork continued. “They don’t have any data. We have data. We know what our athletes have earned the last two years.

“When people say that, I think they’re just talking with an uninformed background of information because people just throw things out.”

Saban “threw out” a couple of other curious opinions concerning the impact of NIL.

Perhaps the most brow-raising was his assertion that college sports is not a business.

“It’s not really a business. Nobody takes a profit,” said Saban, whose annual salary is $11.7 million.

But why let insignificant details pollute the narrative?

College football is business. Big business. Business has been good in Alabama. When Saban complains about the NIL dealings of rivals — often while simultaneously bragging about Alabama’s NIL dealings — well, he’s just trying to protect his business.

But A&M and other programs are in business, too. And the Aggies are prepared to pay the price of doing business in today’s college football. Proposed changes to Texas state NIL laws figure to aid A&M’s business ventures.

“We said from the beginning we’re going to embrace all of it,” Bjork said. “We’re going to embrace fundraising, ticket sales, sponsorship, NIL, supporting our student-athletes…

“We have not been able to be involved in (NIL) based on the Texas state law. That law is now going to change. We think the governor (Greg Abbott) will sign it. It will allow the institutions to support the athletes even more so we can be more involved in it.”

That may cause Saban even more angst.

Perhaps he’s again peering into the future and doesn’t like what he sees.